Psychopathy is perhaps one of the most referenced mental illnesses in pop culture yet also one of the most misunderstood in society today, still. Film characters like the Joker, Hannibal Lecter, and Jason Voorhees have led us to believe that individuals with psychopathic traits are indefinitely cold-blooded killers devoid of any conscience or empathy.

But do these portrayals bear any semblance to the true nature of this condition?

Psychopathy is a spectrum disorder that is evaluated by a mental health professional using the Hare Psychopathy Checklist, developed in the 1970s by Canadian psychologist and researcher Robert Hare.

The checklist assesses patients for 20 traits that psychologists believe constitute clinical psychopathy, including: superficial charm, need for stimulation, manipulative behaviour, lack of remorse/guilt, parasitic lifestyle, promiscuous sexual behaviour, impulsive, irresponsible, and juvenile delinquency, to name a few.

Each characteristic is judged on a three-point scale, with zero indicating the behaviour never occurs in the individual, one indicating it applies sometimes, and two meaning it fully applies.

As noted, the test can only be accurately carried out by a mental health professional and results are tallied at the end on a scale of zero to 40. A patient must score 30 or above to be considered a clinical psychopath. For reference, Ted Bundy scored a whopping 39.

Psychopathy is a collection of traits and not a diagnosis in and of itself. Psychopathy overlaps with a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD).

“Most people might assume antisocial describes someone who is reserved, a loner, keeps to himself, etc. However, this is not the case in ASPD,” explains Dr. Prakash Masand to Healthline. “When we say antisocial in ASPD, it means someone who goes against society, rules, and other behaviors that are more commonplace.”

The umbrella term of ASPD also encompasses another illness that psychopathy is often confused with: sociopathy. Though both illnesses do share similarities with one another, they are quite different in terms of how they manifest themselves in behaviours.

“I was always under the impression that ‘sociopath’ and ‘psychopath’ were synonymous,” says second-year health science student Emma Von.

“I think the reason for this is because people relate violent and criminal activities to both of them, and that’s usually the only time it’s brought up. No one ever stops to question why there would be a difference in naming until they find out the science behind it.”

Researchers believe that sociopaths are mainly the result of environmental challenges, such as growing up experiencing emotional abuse, physical abuse, or other forms of trauma. Unlike their psychopathic counterparts, sociopaths do have a conscience, but a very weak one. They often rationalize their wrongdoings and make it known they do not care how others feel.

Additionally, sociopaths typically have an irregular work history and may commit crimes impulsively or without any planning, leading them to get caught more easily. A clear disregard for right and wrong, pathological lying, callousness, cynicism, along with a hot temper, and violent outbursts are just some of the factors that can make having relationships with them fairly difficult.

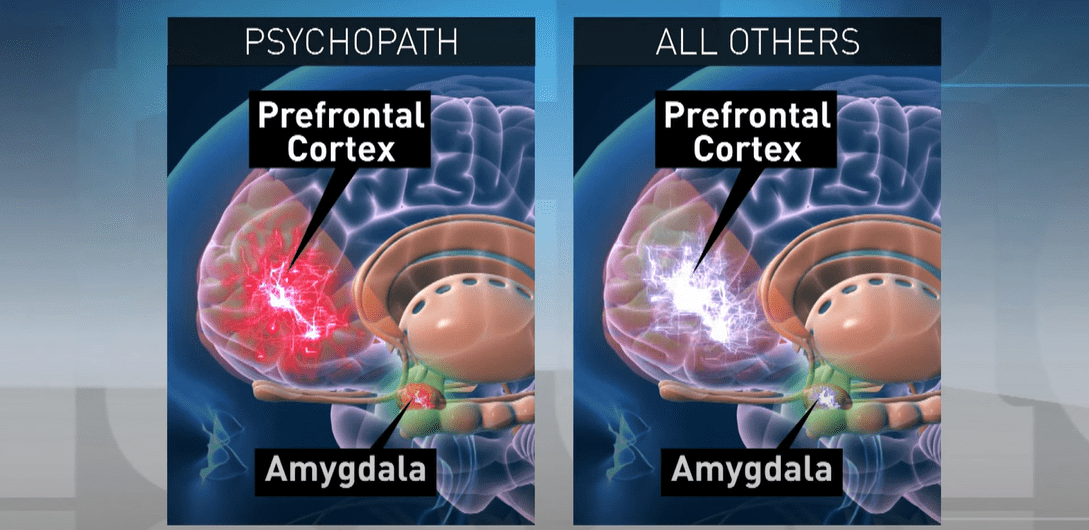

Psychopathic traits, on the other hand, are believed to be a cause of genetic predispositions such as physiological brain differences (i.e. reduced connections between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala — the parts of the brain responsible for empathy, guilt, fear, and anxiety). This allows them to have a severely reduced fear response and makes it near impossible for them to feel any kind of guilt or remorse for their actions, no matter how disturbing they might be. These individuals also have difficulty forming deep attachments to people, which may make their relationships manipulative and detached.

Psychopathy is about as common as bulimia, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, and narcissistic personality disorder. Correctional Services Canada reported that 18 to 40 per cent of criminal offenders are psychopaths. They are often well thought-out and calculating when carrying out crimes, actively trying to minimize their risk.

Though highly represented in prison populations, crime is not an inherent part of this mental disorder — of the global population, only about one per cent meet the clinical criteria for psychopathy. Many are well-educated, being able to hold steady jobs while maintaining families and seemingly unproblematic relationships.

In fact, many high-ranking career positions in our society have been shown to attract psychopaths, as their traits may be an advantage in fulfilling these roles.

Kevin Dutton reveals in his book, Wisdom of Psychopaths, how some professions actually greatly appeal to psychopaths. Among some of the more interesting professions were CEOs, attorneys, salespersons, surgeons, and even clergymen.

“It makes sense to me why a lot of these professions would attract people of psychopathic natures,” says third-year economics student Mo Rehman. “A lot of the professions on the list are leadership roles with a lot of power and likely require some manipulativeness and intense decision-making to succeed in – all areas that a psychopath would thrive in.”

Psychopathy is a spectrum disorder in the truest sense of the phrase. From criminal activity on one end of the spectrum to some of society’s most renowned positions on the other, it is important for the public to be aware of this mental illness, as information will stray us away from stigmatizing it.

So the next time you host a Friday the 13th marathon because you have a morbid fascination with “psychos”, or even the next time you call your ex “psycho” — remember that you’re not only adding to the stigma, but a non-clinical diagnosis for the sole purpose of a hyperbole really does nothing for the strides made in bringing awareness to mental disorders.