Of those who make them, four out of every five Canadians do not stick to their new year’s resolutions, and over half give up after one month.

These statistics only prove what most of us see as an obvious fact: new year’s resolutions rarely work. So what gives? Why are resolutions so hard to keep? And why is it that we carry on with this tradition year after year?

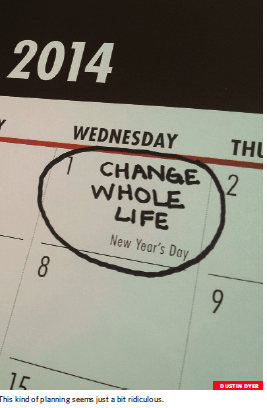

For a lot of people, change means the unknown and something to be avoided, but in the case of new year’s resolutions, change is scheduled, due to start on January 1, and there’s nothing frightening about clockwork. There’s nothing wrong with planning to change.

However, it seems the resolution itself gets lost in the commotion of anticipating and celebrating the new year.

This makes sense, considering most of the fun comes from discussing our resolutions, thinking about how improved we’ll be during the coming year, comfortable in the knowledge that we aren’t expected to do anything until January.

Of course, January eventually arrives and without all the glamour of the holidays, working towards self-improvement just feels more like, well, work.

Committing to more than they can take on seems to be one problem people often make when creating their resolutions.

“We live in a ‘go big, go home’ type of society,” psychologist Dr. Michael Vallis told CBC, in an interview. “And that is one of the big reasons why people fail. They bite off more than they can chew.”

Other professionals who have built their careers on helping people enact effective change echo these sentiments.

One such person is Robin Sharma, who founded Sharma International Inc., a consultancy firm aimed at fostering leadership and positive change within businesses and companies.

In his 2010 video, “How To Make This New Year Your Best Year Yet,” he emphasizes the importance of reflecting on the lessons of the past 12 months, clarifying what one’s goals are for the coming year, and then graduating this all into a plan.

Sharma advises, “[Sequence] all of the things you want to do and all the values you want to live by. Put them into a month-by-month plan, sequencing them so you know in January what you’re going to do, February what you’re going to do.”

Sharma’s advice is grounded in reality. Many of the most common resolutions we take on are actually physically impossible to achieve in a short amount of time.

Losing weight, which is frequently the #1 new year’s resolution in Canada, takes weeks or even months to achieve.

The same is generally true of quitting smoking (#2), sticking to a budget (#3) and saving more money (#4).

Patience, it would seem, is the key, but not everyone has it.

That’s likely why the spike in gym attendance that is seen every January drops off almost completely by mid-February and 85 per cent of people who quit smoking relapse by midway through the year.

Vague goals also cause trouble, as studies have shown that we commit more to specific, explicitly stated objectives, which might mean reworking that mission to “become a better person.”

Our resolutions—and our failure to achieve them—show that our lives are characterized by conflicting priorities.

Almost everyone would agree that getting healthier or spending more time with their family is important, but very often, these goals are usurped by other priorities such as work or friends, or just don’t show their worth fast enough in the new year.

But making a plan and recognizing the inherent work that comes with change, and of course, not biting off more than you can chew are what it comes down to.

Create specific goals targeted to specific change. Because if it was easy, everyone would do it, and nobody would spend so much time talking about it.

In other words: less resolutions, more resolve.