Flynn Daunt

Science & Technology editor

In the scientific community, talk about the matter of space, planets and extra terrestrial life builds excitement.

That’s why the recent discovery of a planet that could, theoretically, support life has left researchers and media prematurely giddy about the thing – even if it’s about 20 light- years away.

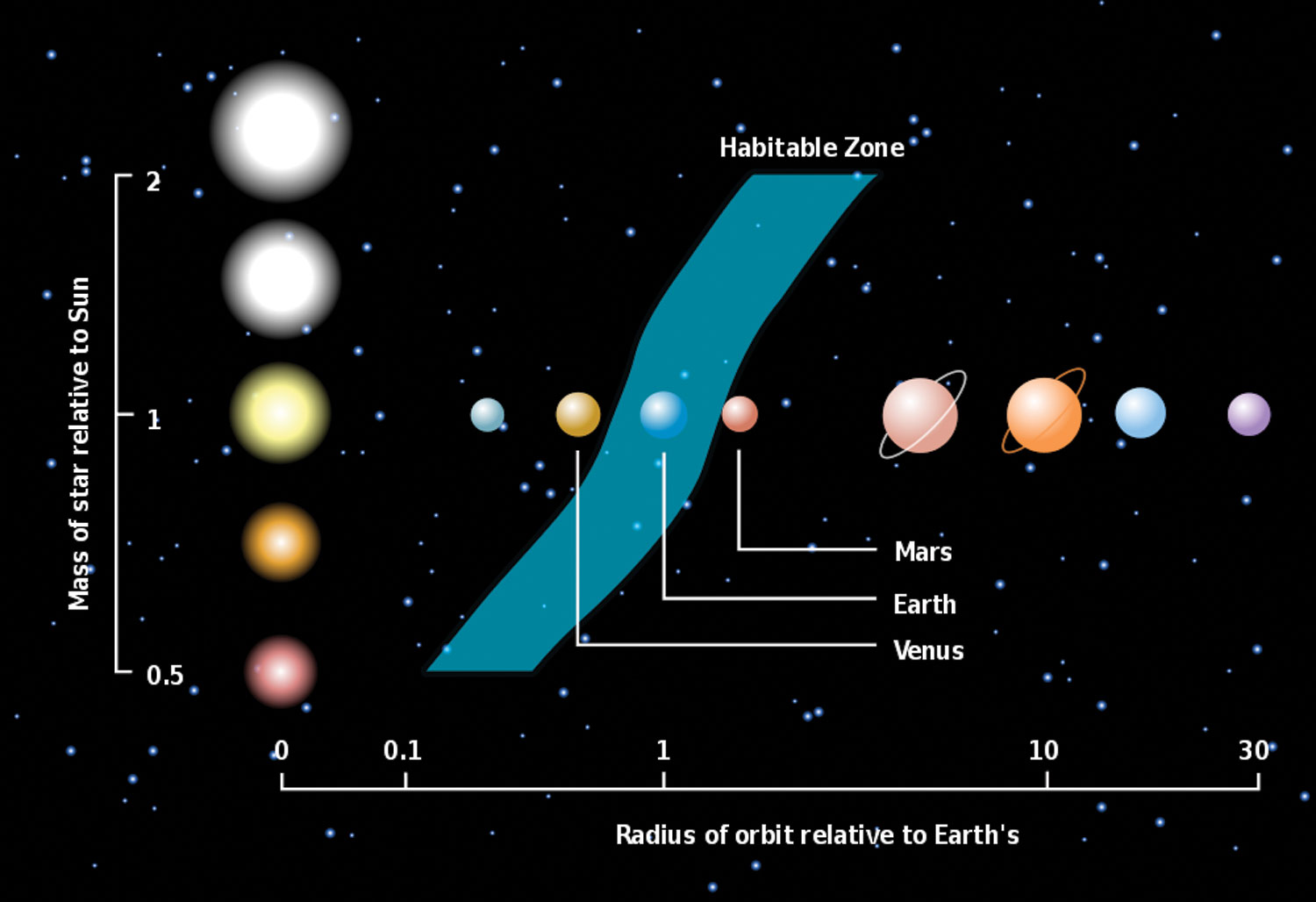

The rocky planet, Gliese 581g, is far enough from its sun so it won’t be too hot and close enough so it wouldn’t be too cold. Like Earth, it is in what’s known as the habitable “Goldilocks” zone, where temperatures would be able to support life; it’s also believed to be large enough to support an atmosphere.

Gliese 581g wasn’t discovered with the naked eye; in fact, it’s so far away that it’s impossible to actually see it. The research team had to use a principle known as radial velocity, which looks for changes in a solar system’s sun, to detect it.

Some scientists, though, are not so giddy about Gliese 581g. They dispute the accuracy of the methods that researchers employ in detecting exo-planets, that is, planets outside of our solar system. Mary Helen Armour, a York University professor of the faculty of science and engineering who teaches the course “Life Beyond Earth,” reminds us that these techniques are not exact measurements.

“All the techniques that we use don’t actually see the planet. We only see the evidence of the planet.”

She explains that, when we use radial velocity to locate planets, we can’t really gauge the size of the planet; we can know only how small it may potentially be. In fact Gliese 581g could be much, much larger than Earth.

“There’s always the possibility that we’re misinterpreting the evidence,” added Armour.

Even if astronomers’ observations of Gliese 581g are true and it is, in fact, in the habitable zone, this does not guarantee life is present on this planet.

“I’m trying to temper everyone’s enthusiasm at the moment,” said Paul Delaney, York’s observatory director. “The notion of life on these planets is pure speculation. It’s nice speculation.”

According to Delaney, we still don’t know anything about the planet’s atmosphere, which can make all the difference. Both Mars and Venus are earth-like planets close to our sun’s habitable zone but they vary widely in atmospheric composition and are unlikely candidates for life.

From the evidence, Gliese 581g would be tidally locked, like our moon – one side would always face the sun. This would mean life would likely exist in “The Terminator” zone between the light side and dark side.

This has not stopped Steven Vogt, the researcher who led the team that discovered the planet, from saying he was sure that life exists, or existed, on this planet, quickly spawning artists’ impressions of the world and talk of how this life would look.

Delaney, like many other astronomers, is cautious. “It is only his opinion. There is nothing to support that in any of our data,” said Delaney. “There is an awful lot of things flying around the world [from people] who have taken that quote out of context and run with it.”

This isn’t the first time the Gliese system has been in the spotlight. Gliese 581c, another planet in the same system, was being paraded about as Earth 2 back in 2007, before astronomers looked closer and found it less and less likely it’d be a candidate for alien life. Delaney warns us that we still don’t have any solid evidence that this planet has any life.

“Everyone wants to think that it has life, but we have no evidence to support that there is life in the Gliese system at this time,” said Delaney.

Armour believes that the discovery of the planet is not without its merits. What the discovery does show is that planets are much closer to us and more numerous than we thought.

“It’s interesting because it shows that relatively close by we found a planet that’s potentially habitable and this makes us more optimistic that there could be a lot of those types of planets around,” said Armour.

Delaney agreed, saying “It tells me that planets are really very common. And that’s been a big question for the last 15 years.”

Delaney adds that there could be millions to hundreds of millions of Earth-like planets in our galaxy.

“We thought, hoped, wanted for planets to be common. We’re beginning to really see evidence to support that conjecture.”