Arfi Hagiyusuf, contributor

When I first came into contact with the term anti-blackness, a fury of emotions came over me, but what I most remember is relief. Relief that what I had been feeling and experiencing for the past two decades was all valid. Relief this wasn’t something that I was imagining or fabricating; it was real.

I grew up in what most people would consider a diverse neighbourhood. Most of my classmates’ parents and grandparents migrated to Canada from hotter climates as did mine. We shared the same morals, religion, and class bracket. Despite this, for most of my schooling I felt alienated. I’m still reconciling my sense of alienation today.

My first encounter with anti-blackness happened too long ago for me to remember, but I do remember my most jarring experience. I was in grade 10 planning a trip to the mall with my friends and one of my friends, a non-black person of colour, said that we could all get a ride with her mother because she was very progressive and liked black people. This was paired with what appeared to be a genuine smile, leaving me confused and shocked, but I still felt obliged to thank her and her mother for their progressiveness. Needless to say, this was one of the most uncomfortable experiences I have ever experienced.

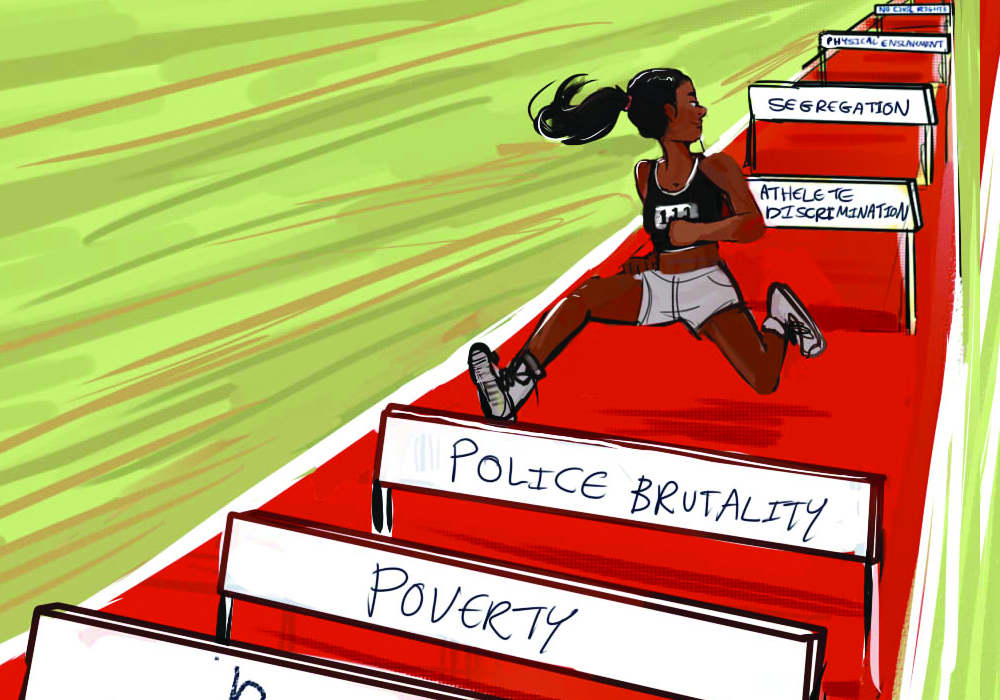

Anti-blackness goes deeper than uncomfortable exchanges like this. It happens both unconsciously and consciously and to limit it to mere vocal exchanges simplifies this. It must be understood that the hierarchy of racism is built on white supremacy which relies on the stark opposition of blackness, leaving all others to fall neatly into this hierarchy based on their proximity to whiteness. This hierarchy allows non-black POCs to be propellers and agents of anti-black sentiment and racism

What is especially detrimental to black bodies is the constant equalization of POC. The equalization that we all fall under the same umbrella and share similar experiences and therefore we are all allies. This is simply not the truth and it erases the experiences of black people.

Consider the expulsion of Black Dominicans and Haitians from the Dominican Republic, the criminalization of blackness as a tool of disenfranchisement. Even here at at York’s Federation of Students annual General Meeting in November, an increase of $5,000 to show solidarity and support with students of Mizzou received mixed reviews. Numerous students of colour appeared and sympathized with the black struggle, but in the same breath they dismissed the motion. This masquerading of solidarity is arguably is more potent than external anti-blackness because complacency is more dehumanizing when perpetrators have experienced anti-blackness themselves.

As a black woman, to look back on my experiences and critically analyze and pull at every seam is tiring and nearly impossible. When you have been black all your life, exchanges become normalized and you cannot differentiate whether these have been tainted with anti-black sentiment. I have a lot of these moments where I wonder if what I am thinking is a genuine opinion or a product of internalized hatred.

The notion that all POCs are equalized through simply the melanin in our skin produces a false sense of emancipation. The guise that there is no way to perpetuate racist attitudes as a POC is also false. Not all POCs are disenfranchised equally and to continue to perpetuate this train of thought not only erases the severity of the mistreatment of black bodies, but repeats it. It is convenient and much too easy to only blame white folks for the disenfranchisement of black bodies. Though they may be the root of the problem, many branches and similar species have grown since.