When I open up the “new releases” tab on Netflix or Disney+ or any other streaming service, I inadvertently find myself doing a double take at the eerily familiar list of titles. Was there some kind of glitch? Did they accidentally swap all the brand-new film and TV titles with the classics?

No, there’s been no mistake. Over the last few years, remaking, reimagining, and spinning-off classic (and sometimes obscure) shows and movies has dominated an ever-increasing swathe of the market.

This isn’t an entirely new phenomenon, with remakes like The Karate Kid (2010) starring Jaden Smith and The Amazing Spider-Man (2012) with Andrew Garfield coming to mind as pretty popular in the previous decade. But recently, rebooting has seemed to escalate to a fever pitch. It’s not just the Disney princess movies and action classics getting remakes now. In 2018, Den of Geek released a list of 121 highly anticipated reboots and remakes that had been announced as of then — 121.

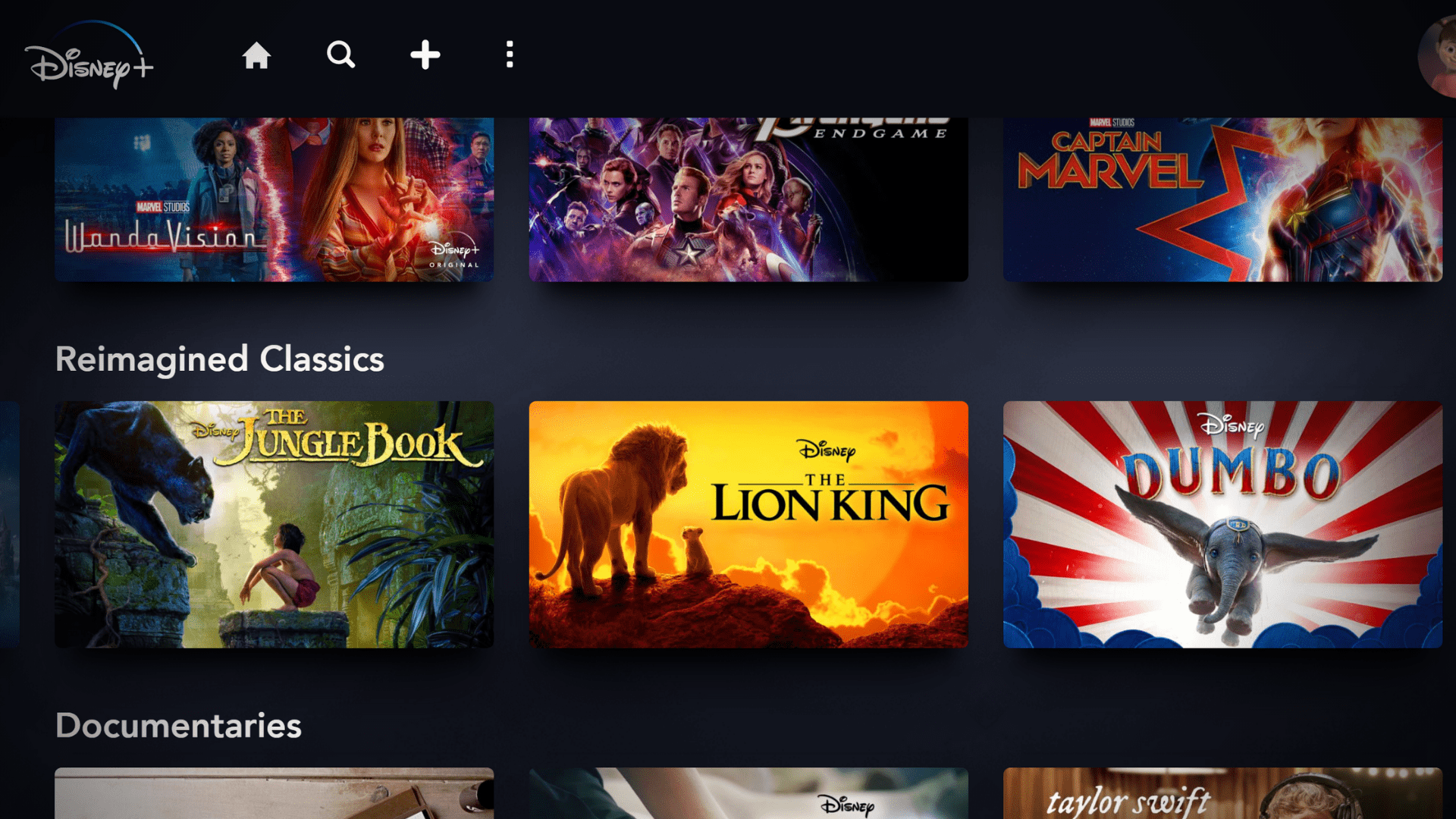

That staggering number has only been added to in the next three years, and nothing serves as a better example than Disney Investor Day. On December 10, 2020, the media behemoth unveiled its line of upcoming projects across in a massive presentation, garnering hundreds of thousands of social media shares and a massive amount of buzz.

Within this dazzling display of the hottest, freshest, buzziest movies and TV series to hit the Internet, the number of remakes were too many to count — Diary of a Wimpy Kid, Cheaper by the Dozen, The Little Mermaid, Night at the Museum, and more all made the list. Buried within the litany of Disney’s newest content were tons of offerings that are technically not new at all.

“I understand the appeal of wanting to do a remake,” says Yusra Kureshi, a first-year biochemistry student at the University of Waterloo. “You bring back an audience that perhaps may have been lost over the years.”

For the casual viewer, it might feel like at this point in time, one can name literally any movie or TV show, and learn that they’re remaking it. Whimsical classic The Secret Garden? Yes, they remade it in 2020. The flashy, relatively new and popular Suicide Squad movie that came out in 2016? There’s a remake scheduled for this year.

A gritty, dark, live-action Powerpuff Girls remake featuring them as disillusioned adults jaded by a traumatic childhood fighting crime?

No, I didn’t make that up.

It’s clear that the realm of remakes has expanded beyond anyone’s wildest dreams — or maybe nightmares.

As we escalate to these dizzying, previously unforeseen heights, the time arises to pause and reflect on some major questions. Who asked for these remakes? What do they mean for the film and TV industry, and for the creatives who make their living there? And lastly, and perhaps most importantly, are audiences enjoying them?

ONCE UPON A TIME

As the list of remakes begins to span from high-profile to obscure, predictable to bizarre, it begs the question of why. Why are major production companies banking on these, and who is their audience?

“Adults crave nostalgia,” Kureshi succinctly remarks.

Professor Natalie H. Coulter, who is the director of York’s Institute for Digital Literacies (IRDL) and specializes in the promotional ecologies of children’s media and entertainment, corroborates this point. She tells us three core reasons why remaking classic or popular films and TV shows marketed towards young people has gained popularity recently, and nostalgia is first on the list.

“It’s safe,” she says. “They know they have an almost guaranteed audience of people who will watch it for nostalgia.”

A gleaming example of the success that accompanies a guaranteed audience, ripe with nostalgia, is 2019’s The Lion King remake. The film was an undeniable success, and was essentially an exact remake of the original classic revered by families everywhere, simply remastered in shining CGI/quasi-live action visuals. It now boasts the mind-boggling title of the highest-grossing animated film of all time, raking in over $1.3 billion and outstripping even the Frozen franchise. This might never have been possible without the foundation and nostalgia of the original classic.

Nostalgia isn’t the only driving factor behind rebooting films and shows. Coulter identifies a second key factor motivating the creation of more remakes.

“It is easier to market,” she adds. “They don’t have to explain what you are marketing. People already know the IP (intellectual property) or premise, companies just have to remake the story.”

This appears to be a guaranteed cheat code to success — if it ain’t broke, why fix it? If a film or TV show has proved itself once as capable of generating popularity or a cult audience, production companies may feel they can create something similar (or identical) with low risk involved. For instance, Disney doesn’t need to worry about audiences having trouble puzzling out the backstories of the Fantastic Four family in the upcoming remake — not when there’s already been two other versions of the same movie in 2005 and 2015.

Coulter’s final reason focuses on the fans: “Fans are invested in the topic and might help promote and circulate it more easily on social media,” she says.

In some cases, these fans are actually the number one force behind the creation of a remake. The upcoming Disney+ TV series based on Rick Riordan’s internationally best-selling Percy Jackson and the Olympians book series is a perfect example. Long ago, the first two books in the series were adapted into films — The Lightning Thief (2010) and The Sea of Monsters (2013). The two movies received mixed to negative reviews, and majorly disappointed the series’ massive fanbase of young adults. The spark fizzled out, and the remaining three books in the series were never adapted.

That is, until the fans took the reins. In 2019, fans on Twitter spontaneously started a trending hashtag called #DisneyAdaptPercyJackson. Readers of the books pleaded with Disney, envisioning their favourite book moments that the original films hadn’t captured, and even swearing their undying loyalty to Disney in exchange.

Months passed, and lo and behold — to the delight of thousands of fans — a Disney+ remake TV series was announced.

BEHIND THE CURTAIN

While it’s clear that remakes can be tremendously profitable, it’s less certain what this means for the artistic aspect of the film and TV industry. As remakes dominate the scene, what are the implications for aspiring writers and filmmakers, or for creative content as a whole?

Reann Bast, a second-year screenwriting student at York, weighs in. “As a writer, I think this can be a good thing and a bad thing. I think it can lead to a lack of new stories exposed to the world, but it can also be a good way to diversify old movies and for new writers to get their foot in the door.”

These concerns about the suppression of budding new stories and independent voices appear to be a recurring theme. “I worry about old, recirculated content leaving little space for new content, and new talent,” adds Coulter.

However, in her position as someone who studies the ecologies of entertainment, Coulter refrains from making blanket statements about what might be good or bad for the industry as a whole. The truth, she says, is much less black-and-white. “I try to avoid thinking about things in these terms — positive or negative — as it is much more complicated than this.”

Coulter cites several aspects of remakes as signs that can be considered positive for the industry as a whole, including financial success, dominating the screen, and increasing diversity.

Bast echoes the relevance of diversity as a potential benefit remakes can have for the industry.

“The main objective of a lot of them is diversity, like the Ocean’s Eleven remake Ocean’s 8 (2018) with the all-female cast. While it wasn’t a great movie and definitely not as good as the originals, it was fun to watch and I loved that it was all women,” she says.

“I know a lot of criticism comes from fans of these popular movies like Ghostbusters (2016), and the biggest reason is because it’s being made with cast changes and with inclusivity and diversity in mind. While I think these are weak and money grabbing ways to showcase an attempt at diversity, I also have to give credit to the attempt. Regardless of the negative critiques, I will continue to watch these remakes.”

Bast also brings up another unique intention that remakes might have for artistic works. “Making them more palatable for the modern day.” She believes this could involve removing the racist caricatures from old films such as Disney movies, however, she doesn’t believe this is a primary motivator.

“Instead, it seems we keep getting the same stories shoved down our throats with the bare minimum of changes.”

THE CROWD GOES WILD

Ultimately, films and TV shows are created to entertain audiences. As the remakes pile up on streaming services and in theatres, the question is: are they still watching?

When it comes to the movies and shows they grew up with, audiences have very, very, very strong opinions. A firm analyzed the ratings of critics and audiences for original movies versus their remakes, compiling Metacritic data for critics’ opinions and IMDb ratings for ordinary people’s opinions.

According to the data, critics preferred 87 per cent of the original movies to their remakes, while audiences rated a whopping 91 per cent of originals as better than their remakes.

It seems that just as nostalgia might send people to the theatres in droves to watch remakes, it also seems to inversely correlate to ratings of those films. Loyalty to the original content appears to be almost unwavering. Remakes serve as a reminder of that loyalty, albeit sometimes reflected in the vehement disapproval of fans.

“My opinion is that they never get a remake right,” says Kureshi. “People would like remakes a lot more if they at least held some consistency, but were still fresh. Like with Mulan (2020), they took out everything people liked and then completely changed the premise.”

Mulan comes up over and over again as an example of a remake that incurred the wrath and disappointment of fans. The 2020 live-action remake of the 1998 animated classic had its box-office earnings hampered by the first onslaught of the pandemic, but that doesn’t seem to be the root cause of disappointment. Rather, audiences took major issue with the fact that the remake cut out elements that were beloved in the original, such as all the catchy musical numbers, the stalwart commander Li Shang, and the beloved tiny dragon Mushu.

“Often they mess remakes up completely, just like Mulan,” says Bassam Rashid, a forensic science student at OTU. “I haven’t watched it, but I know enough to know it’s not Mulan.”

Moreover, audiences took issue with major directorial choices, including the decision to film in the Xinjiang region of China, where over a million Uighur Muslims have been facing extreme ethnic persecution and detainment.

Bast cites the film as an example of how Disney’s new remakes set “money grabbing” as their one goal.

“It is fairly clear this is the case based on Disney’s newest remake — Mulan. They did no research, filmed in terrible places, the diversity was only on screen, and they made Disney+ members pay extra to watch the film before releasing it to the platform for everyone,” she says. “I think these kinds of remakes are negative and there are so many other stories to be told, we don’t need to keep seeing stories from the same people, fictional universes, and existing stories.”

For fans who grew up with the original movies and shows, seeing remakes that appear to disrespect the source material or make gratuitous changes can be a painful experience.

“Live actions actually take away a lot of the charm and creativity from animation. So, watching the live-action remake doesn’t even give me the same charm as the original even if it plays out beat for beat.”

Munira, a fourth-year urban planning student who would like to only be referred to by her first name, discusses issues with what she calls “grown remakes” of original movies and shows. “Something that succeeded well with the original — usually PG — plot, has been completely flipped and turned into a lewd mess that completely destroys the original storyline, just to sell sex with recognizable names.”

Kureshi says major differences hold her back from enjoying remakes. “I don’t mind a remake. Some things I want to see on screen again, but not in the ways they put them out. If they just listened to the overwhelming opinions of people on the internet, then they’d get a good feel of what their audience wants from the remake or is looking forward to.

“The problem here is the differences are outrageous,” she adds, “With Fate: The Winx Saga (2021),” (a remake of kids show Winx Club (2004), “they whitewashed it and took the whole pretty magic aesthetic away. Nobody wants to watch it anymore because it doesn’t remind them of when they first watched it, but it also doesn’t bring anything new to the table.”

Outside of unfaithfulness to the original, lack of freshness appears to be a major driving factor behind audiences preferring originals.

“They haven’t been executed well,” says Munira. “There’s a lot of potential, especially with Disney movies, but it’s almost boring seeing the exact movie play out just with real people. Live actions actually take away a lot of the charm and creativity from animation. So, watching the live-action remake doesn’t even give me the same charm as the original even if it plays out beat for beat.”

Bast adds to the discussion surrounding laziness and boredom in remakes.

“I think remakes are the result of a greedy, lazy, capitalist Hollywood,” she says. “How many times do we have to see Cinderella on the big screen?”

Despite these multifaceted and numerous criticisms, there are a few things that stand out to some fans as positive aspects of remakes.

“Sometimes they remake the show and use modern assets, but still manage to capture the theme and atmosphere of the original, which is what I like in remakes,” says Rashid. “I also think when a director adds some of their own hidden details, maybe an Easter egg to their past works, or maybe they’re paying tribute to the original and adding an Easter egg to the original movie.”

Aishah Ahmed, a second-year health science student, says the rare remakes she likes have some key factors in common, and they navigate a fine balance.

“Usually I don’t enjoy remakes, just because they don’t do justice to the original film or show,” she says. “But the limited remakes I do like are the ones that don’t change the main turning points or huge events from the original and stay true to the story — specifically if the plot and ending of the original was loved by the majority of viewers.

“I liked the Aladdin remake (2019), because even though they added new things to the story, they still kept all the main turning points from the original without removing any significant events,” Ahmed adds.

THE SHOW MUST GO ON

Through all of this, it’s clear that fandoms and the abiding love of excellent films and shows is an incredibly powerful force. When it comes to remakes, we can see that this force can quite literally make them (The Lightning Thief) or even break them (Mulan).

What appears to dictate this is ultimately how well-preserved or well-utilised the core spirit of the story is, no matter which medium it is distilled by.

York Professor Geneviève Appleton teaches a course called The Biology of Story, about “how we work with story and how story works with us”, and is producing an interactive documentary of the same name written and directed by the late professor Amnon Buchbinder.

She examines the concept of a remake in poetic detail. “I think the intention and approach to remaking any work of art is what matters. If the aim is to replicate the original in order to capitalize on its success, that can feel parasitic and thus disturbing to the audience,” says Appleton, who began her career as an actress in works like The Kids of Degrassi Street (1979) and Anne of Green Gables: The Sequel (1987).

“An embalmed cadaver can never take the place of a departed beloved, but if the aim is to partner with the original in the creation of a new life,” she says, “that can be deeply satisfying, and have great value to the evolution of the oeuvre of humanity.”

Whether or not a remake retains that spirit and core intention of the original can eventually determine how much it’s appreciated by fans, and how history might view it as a work of art.

Ultimately, Disney Investor Day is one of countless proofs that no matter how many controversies and debates arise as to whether or not remakes are good or bad—or even if they should exist at all—studios are going to keep on making them.

As the next 121 remakes or so come down the pipeline, all of us armchair critics will undoubtedly have our work cut out for us.

All we can do is dim the lights, sit back, and enjoy the show — again.