As the 2012 fare increase upsets the public, Jeson Khan investigates a deeper problem growing within the essential service

Jeson Khan

Contributor

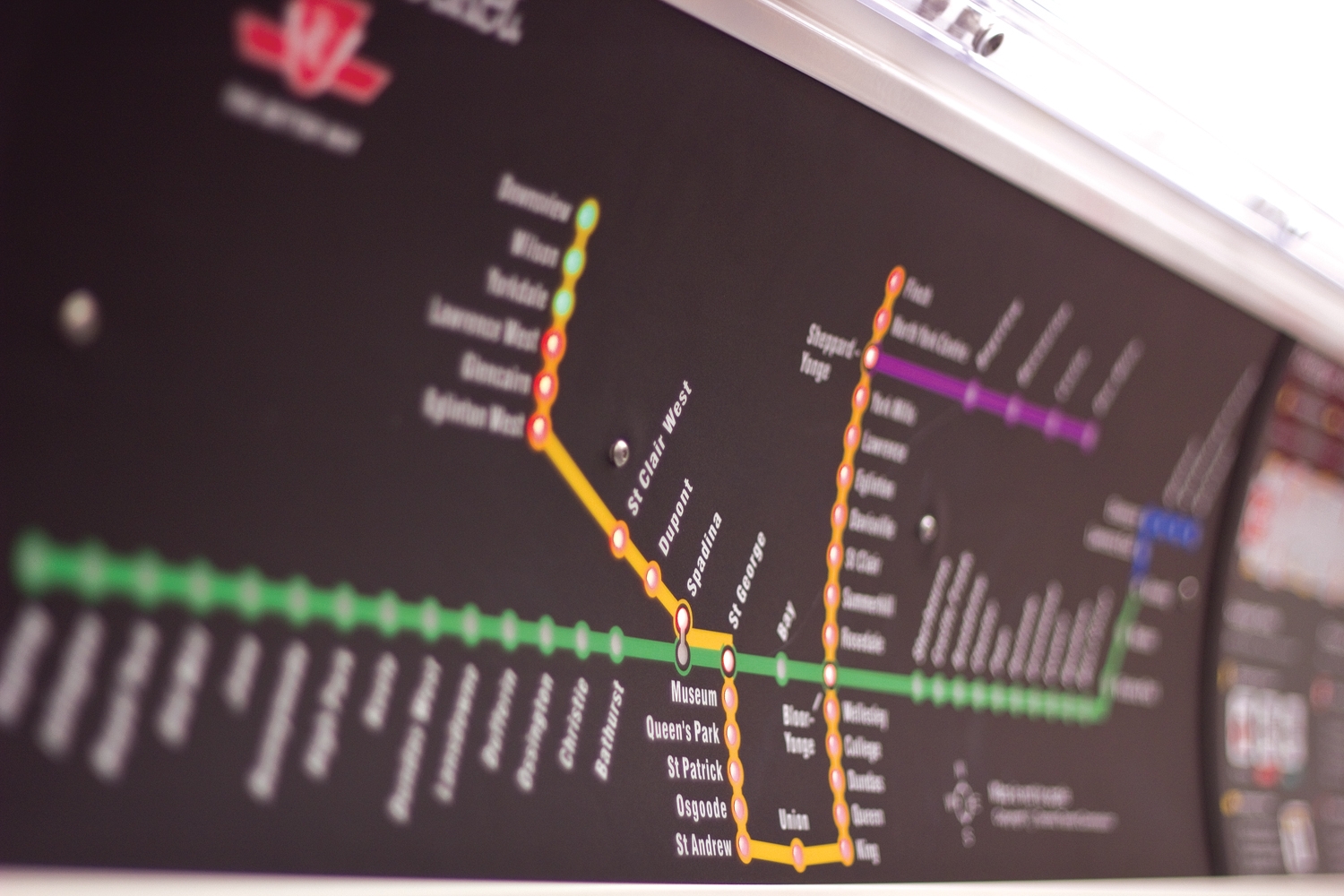

You guys really suck at your job.” TTC rider Jennifer Foulds joins the others in the heat of the city hall argument. The mood in the room is tense. Two groups sit divided in the 2012 budget meeting for the TTC. It’s the Torontonians and union president Bob Kinnear against TTC chair Karen Stintz and her commisioners. They debate the future of Toronto’s transit service and how big of an effect the fare hike will have on TTC riders. Foulds continues, adding a fare hike will add up over the year and riders, like her, will be angry.

But despite all the comments and arguments, the TTC commissioners vote and approve a 10-cent fare increase on adult tokens and a pro-rata increase on other fares for 2012, hoping it will raise $30 million to cover a $21-million shortfall in the budget.

Councillor Marie Augimeri remembers being outnumbered during that December 14 meeting. She was the only councillor out of eight to vote against the fare hike. “I voted against [the fare raise], because we are increasing the fare and cutting services; where before I did vote for a fare raise only because it would have improved the service,” says Augimeri. Her colleagues did not share her views.

Other TTC commissioners, like John Parker, felt that cutting and increasing fares equally would be the best option. Commisioner Parker says they had “some options.” They could increase the fare, or cut services, or do a bit of both.

“The TTC is going through tough times just like everyone else and cutting services wouldn’t be the best option,” admits Parker, “Neither is increasing the fare by a larger amount; that’s why it’s best to settle in between.”

Today, York students and the rest of the TTC ridership deal with higher token prices and pricier metropasses, both of which might rise in the coming years. Services are also facing drawbacks, meaning riders will deal with more crowded buses.

The TTC wasn’t always like this.During the 1990s fares were as low as $1.20. Torontonians were proud of the service. This was before the election of Ontario Premier Mike Harris, when the TTC had better funding. Back then, the TTC was funded with higher government support for both their capital budget (such as buying vehicles) and their operating budget (what it takes to deliver the service).

After Harris’ provincial government withdrew funding from the TTC and allocated it to the municipality budget, Harris gave the TTC no other choice. The TTC had to depend on the mayor of Toronto and the city council.

“Ridership doesn’t pay for all [of] this, so you’ve got to rely heavily on city council,” says commissioner Norm Kelly, also present at the Dec. 14th meeting. “What’s the mood of council? To cut back.”

After TTC lost its provincial subsidies, it was up to city council to fill in that gap. That gap wasn’t filled properly.

“With the withdrawal of the subsidies,” commissioner Kelly explains, “there should have been a more business-like approach taken by the TTC.” That did not happen, and the TTC is still not self-sustainable.

Why has the TTC not figured out a solution until now? Kelly says the TTC has accumulated bad judgements from past handling that prevents them from moving forward. “Would you introduce a bus route in an area where you’re not even going to come close to breaking even?” Kelly asks. “The mistake was introducing a bus on a route, where there was not enough ridership.”

With all these cutbacks, what can the TTC do to cut expenses and increase productivity? Kelly breaks down the problem as he sees it. “Right now when we drive [the] buses, they are super buses,” Kelly says, “After rush hour, you know what you see? Big buses with one or two people on. Driven by a union guy, who makes a lot of money.”

At the same time the more subsidies the TTC uses, the more taxpayer money it borrows from the government. The amount of subsidies used so far is more than one billion dollars. The expected subsidy needed for 2012 is approximately $400 million.

Kelly says running the TTC independent of subsides is crucial and ultimately improves the service as a whole.

“I would certainly recommend a thorough investigation and analysis of franchising the TTC on certain areas. And then you [the franchise] figure out where the demand is…That’s what business is all about…serving [the TTC] in a way to make it sustainable and available.”

Franchising the service might make it more sustainable, though it might be difficult to find an interested entrepreneur or a business.

Despite all the challenges the TTC faces right now, Kelly is optimistic. He says that the TTC is already coming up with solutions.

“We got a whole bunch of new stuff coming out,” he says. They’ve taken buses from routes with low passenger counts that weren’t making money. “[We’re] taking those buses and putting them onto routes that are jammed like sardines,” Kelly goes on.

“We are actually improving the service on the lines where the demand is, in a more sustainable way.”

Kelly joins a larger voice saying the TTC must run like a sleek, efficient business. Financially, there is no going back to before the Harris government. From the December 14th meeting, it’s even more unclear whether the TTC can go back to before the Ford government.

Until a real substantive change happens, TTC riders like Jennifer Foulds will continue to be angry, and Augimeri will still be outnumbered during meetings.