On October 10, York welcomed renowned Canadian filmmakers Guy Maddin and Mike Hoolboom to speak about the art of writing and screenwriting, as well as the creative process in general.

It was a full house with the Nat Taylor Cinema filled with enthusiastic film majors. The dim lights and intimate setting made for a comfortable atmosphere. Screenwriting professor Amnon Buchbinder moderated the event and began by giving both filmmakers raucous introductions, emphasizing that the conversations would give students a “deeper grasp of how filmmakers go about thinking through their films.”

Like Buchbinder said in his introduction, Maddin and Hoolboom are filmmakers who have made us “see the possibilities of film in a way we have never seen before.”

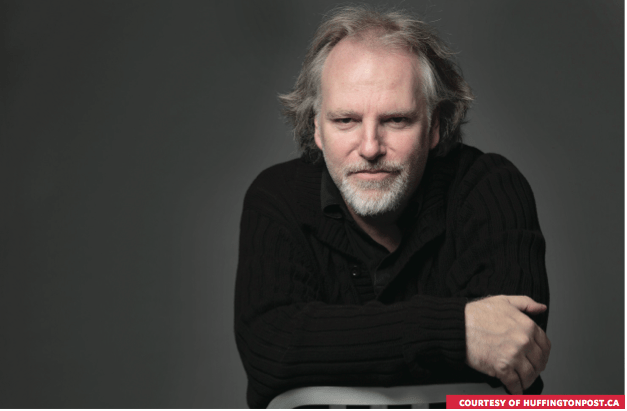

Maddin became the youngest filmmaker to win the Telluride Lifetime Achievement Award, which recognized his odd, madcap film-making style. He has made 10 features including My Winnipeg, which won Best Canadian Feature Film at TIFF in 2007. Maddin uses an interesting approach to script writing. Before making his film Keyhole, he approached artist Paul Butler to propose the idea of writing a script, and Butler responded that he wasn’t a writer.

Much of his recent work focuses in on recreating elements of early cinema that are thought to have been lost forever, albeit making them his own through the cinematic process. His approach worked in contrast with the other speaker.

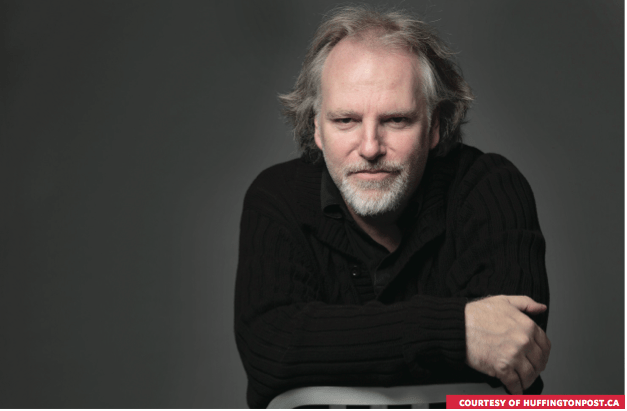

Hoolboom is considered one of the most prolific experimental filmmakers to come out of Canada, as well as one of the best. Since he was diagnosed with HIV in 1988, he has made 22 films, which have gone on to tour and win awards around the world. His advice spoke more to the idea of “killing your babies,” and letting what you remove, rather than add, inform the work.

When writing a script, Hoolboom says the first cut is the deepest. This first cut is the “the shift of perspective,” which could be a monumental change in one’s life or a simple realization of something. When the perspective changes, a script is born. The traditional way of looking at a script is seeing it as a painting — an empty canvas you fill with marks. Hoolboom instead abides by the theory of Douglas Gordon, who says a script is like a sculpture: you have pictures, sounds, impres- sions; and you cut a figure out of it. The way you cut is the script.

For a non-film major, it was an evening well-spent in the company of film lovers interested in the work of stitching together one aspect of the ever-evolving writer’s process.

Tejiri Ohwawa

Contributor