Emma Donoghue’s novel ROOM gives voice to abused women feeling their way out of the cage

Damian Mangat

Contributor

I know what a closed-up room feels like. I know that panic, suffocation, and cold, hard fear reside within its walls. I know that hopelessness exists in the confined space of abuse. As a survivor of abuse and a peer support worker, I hear the stories firsthand from women who have survived sexual abuse or violence within the group sessions at York Region Recovery from Abuse Program (YRAP) in Newmarket. We deconstruct the horrors of our personal histories to build new lives.

The effects of abuse pass on through to the next generation; the children of victims become secondary survivors. Emma Donoghue’s novel ROOM is based on this premise; it expertly captures the psychological, sociological, and political impact of abuse, delves into the paradoxes of the recovery process, and decodes the journey to normalcy.

I often compare living with abuse to living in a birdcage, where the door is unlatched, but victims must feel their way out. Donoghue deconstructs this metaphorical passage through the perspective of five-year-old Jack, conceived during one of “Uncle Nick’s” nocturnal visits to rape his mother in the 11-by-11-foot modified garden shed where the two are held captive. “Ma,” kidnapped at age 19, has spent seven years isolated in ROOM, regularly assaulted by her captor, surviving on scraps of food, a few books, and a television set. The delicate balance of survival thrives on Ma’s maternal instinct to protect her son. Jack is her only hope of crossing the threshold.

“Letting Jack tell his story was my idea in a nutshell,” said Donoghue in a Q & A with The Economist. “I hoped having a small child narrator would make such a horrifying premise original, involving, but also more bearable; his innocence would at least partly shield the reader on their descent into the abyss.”

So why would we choose to read a story based on the Josef Fritz case, where a man locked his daughter in the basement for 24 years? Why would we choose to hear innocent, five-year-old Jack’s perspective on how he sees the world from a tiny cell? Why would we allow our emotions to unravel reading about a woman who, kidnapped at 19, has endured seven years of repeated rape and given birth to a child conceived through that violence? Because abuse and violence against women is real.

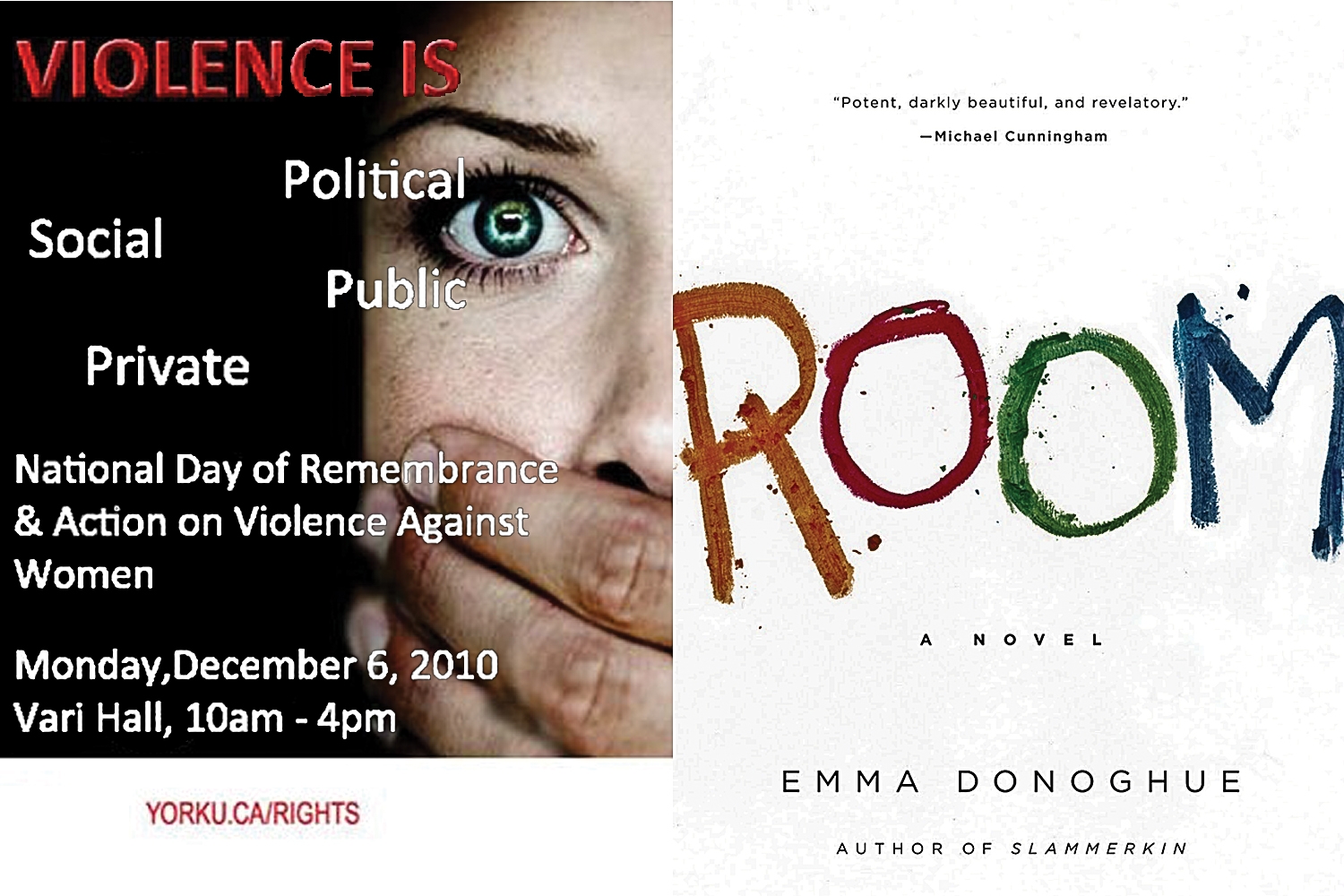

December 6 is Canada’s National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence against Women. While York students rushed from exams to Christmas vacation, volunteers gathered in Vari Hall to distribute purple buttons stamped with the slogan “No Means No.” You probably passed by the silent witness project art installation in Vari Hall representing the 14 women killed in the 1989 Montréal massacre. A plaster motif, signed by students passing by, lay across the floor. They stopped to crouch and pen their statements on the tiles. “I am a survivor! You can be too!”

SASSL, the Sexual Assault Survivors’ Support Line and Leadership, is only one of our campus organizations that petitions to stop the cycle, providing support, hope, and referrals to survivors of sexual violence with a crisis hotline operating around the clock. On December 6, SASSL partnered with the Centre for Human Rights, York Federation of Students, Feminist Action, Amnesty International, and other advocacy groups, for their annual pledge campaign. Despite the grey skies overhead, these volunteers led a march around campus to take back the space.

“I urge the York University community to take leadership in the effort to end gender-based violence,” said York president Mamdouh Shoukri in a commemoration speech. He asked us not only to remember, but to take action in the future.

Reading ROOM and developing empathy for the characters is one example of educating ourselves, opening ourselves to emotions, and fulfilling our personal responsibilities in the world we create on campus, in our lives, and around the world.

An international bestseller immediately upon publication, ROOM was shortlisted for the 2010 Man Booker Prize, the Governor General’s Award, and International Author of the Year, which is to say nothing of the many prizes the book has already won.

Donoghue deserves these accolades for her perseverance in writing a book of this nature.

“[I did] too much—in terms of how much I could bear… [I] pushed myself—to find out how badly and weirdly children can be raised by adults who hate them, what they can survive, and what they can’t,” she continued in the Q & A. Donoghue researched feral children cases, births in concentration camps, children conceived through rape, and children living in prison.

“I researched terrible things that happen to adults [and] the mind-breaking solitary confinement of approximately 25,000 American prisoners at any one time.”

The book will cling to your conscience like wallpaper stained with a grim reality. ROOM induces mixed emotions in the reader that sound like nails on a chalkboard, or in this case, bird claws scratching at the bars of the cage. Upon release, there is another cage to deal with, as big as the world and as tiny as shrunken self-esteem after abuse. The bars, like the scars of abuse, cannot be seen by others, which makes it all the more pervasive. These bars cannot be cut by pliers of the human heart alone, but need time and the support of others, and most importantly, a united effort to prevent it from happening again.

With files from The Economist