Given the limited professional and educational profile of Portuguese immigrants, paired with low rates of post-secondary education, the Portuguese-Canadian community experience has led to unequal levels of participation in Canada’s economy, negative imaging, and a failure to access higher education. This is especially the case for women.

In 2011, the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) task force for Portuguese-speaking students developed a report to examine the 1996 and 2006 Statistics Canada Census, which revealed children of Portuguese immigrants have the lowest percentage of individuals with a bachelor’s degree or higher. Moreover, TDSB research illustrates Portuguese-speaking students had lower percentages of confirmed admissions to post-secondary than the overall TDSB student census.

The purpose of the report was to examine patterns associated with Portuguese-speaking students and consider options to support increasing their achievement. Fast forward to today, the issues pertaining to Portuguese youth persists. In Canada today, one in three students of Portuguese ethnicity fails to finish high school.

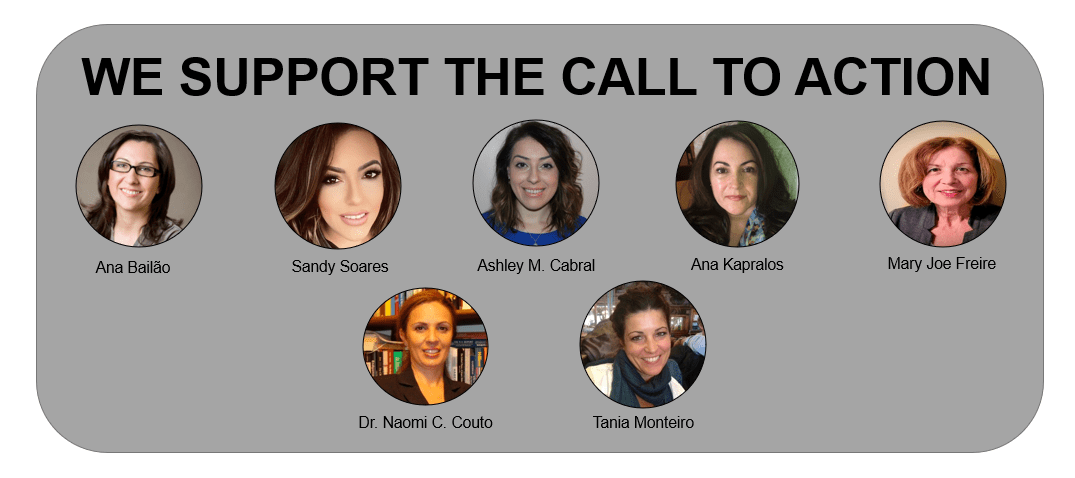

“I am the child of immigrant parents and I beat the odds!” says Sandy Soares, BSW, RSW Early Resolution Officer, Toronto Community Housing.

“My parents immigrated to Canada alone to provide a better life for me, but they did not know that education was the key to a better life. My parents came from an economically disadvantaged village in Portugal where grade three education was the norm so coming to Canada was more about survival — ensuring I had a home, clothing and food and somewhat of an education.

“I chose to pursue higher education because I saw the struggle and exploitation my parents experienced in and outside their workplace, so I wanted more for myself and so did they.”

Tania Monteiro, Assistant Crown Attorney in the Ontario Public Service, explains that she was taught the value of education from her mother.

“I am second generation, born in Toronto of Portuguese parents who immigrated from Portugal in the mid-60’s. Neither of my parents had attained any major milestone of formal education. Notwithstanding that, they very much encouraged me to work hard in school, get good grades, and go on to university. My parents made it clear to me that a life with an education would be less difficult than a life without one.”

“My parents made it clear to me that a life with an education would be less difficult than a life without one.”

It’s also important to shed light on the lack of evidence and research on youth of Portuguese ethnicity, specifically, the leadership positions of Portuguese-Canadian women.

In 2020, women made up 29 per cent of the House of Commons. This is a stark contrast when compared with the overall population of women in Canada, constituting approximately a 50 per cent rate of underrepresentation in the Canadian political profession.

When looking into the labour force participation characteristics of women in Canada, we find that females make up 47 per cent of the Canadian labour force as of January 2021.

Furthermore, women tend to work in industries that reflect traditional gender roles, making up 47 per cent of the employment in public administration, 53 per cent in accommodation and food services, 70 per cent in educational services and 81 per cent in healthcare and social assistance industry.

Taking the Ontario Public Service (OPS) as a case study, we find that of the 66,144 full time employees females comprise 55 per cent (36,509) of the positions, whereas males are 43 per cent (28,779); the remaining two per cent are classified as undefined. Of the full-time employees in the OPS, only 1.5 per cent (453) have identified themselves as Portuguese.

There is a clear lack of leadership positions occupied by Portuguese-Canadians in public service and, in general, women in government.

“The underrepresentation of Portuguese-Canadian women in government, business, and academia is still a reality today. It has persisted intergenerationally, but through my own experience and that of others, we are seeing progress,” says Ana Bailão, Deputy Mayor, Toronto City Councillor for Ward 9 (Davenport).

“This progress is linked inextricably to collaboration, mentoring and hard work, but if we are to sustain and increase this forward movement a lot of work must be undertaken in the present and near future.”

With the research available, there is a lack of data to effectively examine and provide a deeper understanding of the Portuguese community, especially women.

In many governmental reports, statistics regarding the Portuguese community are often amalgamated under “European”, “Southern European”, or “white.” Because of this, the community’s concerns (i.e. social justice, economic) for women are not highlighted for policymakers.

While there are fantastic works to help continue the conversation, there is still minimal research focused on Portuguese-Canadian women.

“Cultural expectations to leave school, and the lack of support in the school system, did not define me nor hold me back … I am one of the lucky Portuguese immigrants who ascended to a leadership role in the OPS.”

Mary Joe Freire, Interim Chair of the Human Rights Legal Support Board of Directors, explains: “As women, and just because we are women, our lifelong journeys are fraught with many challenges. My lived experience as a woman, born in the Azores, Portugal, was dominated not only by gender inequality, but by other systemic barriers to success. Luckily for me, and for my siblings, our parents instilled in us confidence in our ability to one day pursue post-secondary studies. We all did!

“Cultural expectations to leave school, and the lack of support in the school system, did not define me, nor hold me back. Resilience was essential to achieving success. I am one of the lucky Portuguese immigrants who ascended to a leadership role in the OPS. I owe my success to former OPS leaders who were truly enabling leaders.”

As a Portuguese-speaking Canadian woman, I ask for support in the Portuguese community through three commitments:

- For governmental action in assisting Portuguese-speaking Canadian woman;

- For enhanced woman-to-woman community assistance through mentorship programming;

- For every woman thinking they are not enough, to realize they are

“Drawing on my experience, I encourage and challenge other leaders to lead the charge on eliminating systemic barriers and biases, creatively implementing new support systems so that everyone has greater access to opportunities for success,” adds Freire.

“Together, let us unite in our efforts to imagine and create a future in which everyone feels that they belong and can succeed.”

However, certain research has illustrated that Portuguese-speaking students may feel their identities are associated with working class jobs and labour (e.g., construction for males and domestic and industrial cleaning, as well as working in bakeries, for women).

“My mother impressed upon me that a woman without an education would always be more vulnerable than a man without an education,” explains Monteiro. “My mother grew up in an improvised and badly abusive household. She made sure that I understood that education was a cloak of protection a woman could wrap herself in to insulate against the risk of a life of poverty and violence.”

The effects are real, and I myself have struggled with this forced identity. This dichotomy of what I was expected to be (my ethnicity and lack of cultural capital) and what I could be (educated and professionally mobile) is something I see endlessly repeated in the Portuguese community even today.

“Given my upbringing, it’s come as no surprise to my parents that I became a lawyer who works for the government. It only made sense that becoming an educated woman meant getting a job that allowed me to help people through the work of the public service,” says Monteiro.

Some employers do a fantastic job at providing employees the opportunity to create their own networks in order for them to engage with others. For instance, within the OPS, there exists the East Asian Network, FrancoGO, HolaOPS, the South Asian Network, as well as Women in Government.

“It was the power of access and knowledge gained from mentorship and networks that proved impactful as I advanced in my career and education to guide my journey.”

Throughout the entire OPS, however, there exists on record about 453 employees that have identified themselves as Portuguese, but there is no employee network for them.

Pierre Bourdieu, a French sociologist, coined the term “cultural capital” to reflect the accumulation of knowledge, behaviours, and skills that a person can tap into to demonstrate their cultural competence and social status. As adults, cultural capital helps individuals to network with other adults who have a similar body of knowledge and experiences, and who in turn control access to high-paying professions and prestigious leadership roles.

When applying Bourdieu’s theory in the workplace, new employees are often eager to grow and develop their skills in hopes to climb the ladder and find themselves in a position of leadership. The existence of support programs and community involvement initiatives that share experiences and lessons learned play a critical part in one’s career development.

Ana Kapralos, PhD Candidate, Director of Program Modernization and Appointments of the Ministry of Attorney General in the Ontario Public Service, explains the Portuguese cultural values instilled in her as a girl.

“They included a strong commitment to family, work, and respect for hierarchy and authority. But it was the power of access and knowledge gained from mentorship and networks that proved impactful as I advanced in my career and education to guide my journey,” explains Kapralos.

“I am now committed to serving as a mentor and bridging connections.”

This article is a reflection and somewhat biographical narrative of Portuguese-Canadian women. The items discussed are but one small addition to the narrative here and in no way captures the many factors that contribute to the positioning of where Portuguese-Canadian women find themselves today.

It is meant to shed light on how one tries to carve out a space in a world that has said there is no space for them.

Thank you for writing this article. As a 2nd generation Portuguese Canadian I too have seen the struggles of my peers to complete highschool and to pursue post-secondary. Add to that the cultural expectations of females in the Portuguese Culture it is a wonder that women like me and yourselves did pursue post-secondary education. My parents came here in the 60s for the better life but my mother was fortunate enough to have gone to teacher’s college in Madeira. Although she was not able to be one here, as she made more money working in a factory, she and my father instilled in me from a young age the belief that post-secondary education was the only route for me. They taught me that the Portuguese “work-ethic” needed to be applied to my studies. I was fortunate that they supported me financially in my pursuit of a career in Education. I had many Portuguese Canadian friends who unfortunately were pushed towards a more traditional life of getting married right after highschool and working somewhere that did not require years of “expensive” education/training. Not only should there be more associations but also Scholarships and Mentoring for young Portuguese-Canadian girls.