No Time to Hit Snooze

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Report on the Physical Science Basis published on August 9 2021 has been described as Code red for humanity by the UN Secretary-General António Guterres. Based on an assessment of 14,000 scientific publications, the report’s message is clear: human activities caused the atmosphere, ocean, and land to warm at a faster rate than ever experienced in 2,000 years.

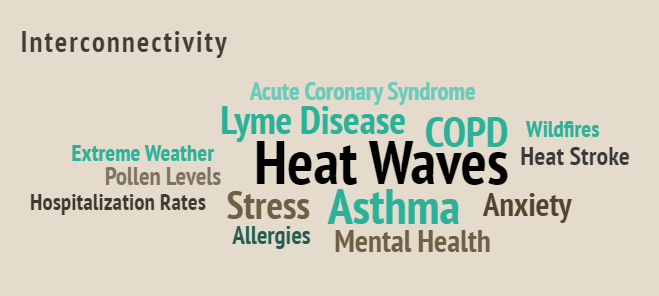

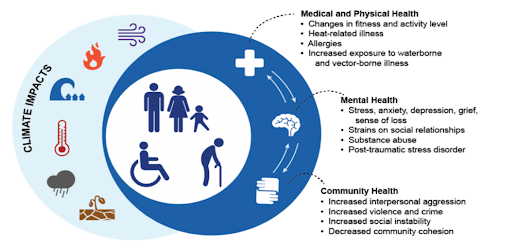

Climate change is not a future threat. It is a present reality and a public health and humanitarian emergency. Severe heat waves, which occurred every 50 years, are now occurring every 10 years. The impacts are seen worldwide — from drought and fires in Southern Europe, Russia, and North America, to flooding in Western Europe, Africa, and Asia. Alarm bells have been ringing — except this time, we cannot hit the snooze button.

The June heat wave in the Pacific Northwest regions of Canada and the U.S. claimed over 486 lives in British Columbia. Without human-induced climate change, we know that these extreme temperatures could not have happened.’

Fanning the Flames of Pre-Existing Inequities

Climate impacts are uneven and intensified by social injustices and inequalities. In Canada, Indigenous peoples and northern communities — including First Nations, Métis, and Inuit — are especially at risk for impacts such as loss of traditional foods, increased reliance on prohibitively expensive imported food, and loss of winter-only roads many communities depend on for survival. These impacts compounded with the transgenerational trauma passed down from assimilation policies is exacerbating physical and mental health challenges. Other inequalities such as housing status, education, and access to resources further contribute to vulnerability.

Socioeconomic inequities faced by new Canadians, refugees, and people without housing exacerbate risks. Children, the elderly, and people with chronic illnesses, cognitive or mobility impairments are particularly vulnerable. These effects are worsened by the intersectionality of socio-economic inequalities and women’s health.

Canadian cities and urban centres are vulnerable to extreme heat. Heat-retaining asphalt, high density living, and limited green space magnify health risks during extreme heat events. Rural communities face health risks due to reliance on natural resources and under-resourced infrastructure, and higher exposure to wildfires. Sea level rise and extreme events such as hurricanes puts coastal communities at risk, and creates potential displacement.

Three Action Areas for the Year Ahead

Young people are taking action in Canada and around the world. As preparations are underway for a safe return to campus, there are three action areas that can shape our planning for the school year:

Students who are passionate about a career in the health sector must seize the opportunity to integrate climate awareness in their future career plans. The Canadian health care sector is amongst one of the least green in the world, contributing to roughly 4.6 per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions in Canada. Over half of health care’s climate footprint comes from energy used for hospitals. Low-carbon Canadian health care needs to be prioritized. This includes supporting Canada’s target of transitioning electricity to 90 per cent ‘non-emitting sources,’ such as hydro, wind, and solar, by 2030, eliminating the use of coal, and reducing reliance on diesel in northern and remote communities.

Students and faculty can enhance learning for a climate safe future and develop adaptation skills. York offers many hands-on learning courses and programs. Students can ask for more programs that prepare for skills that will be needed to build a climate safe society. Climate change should not be siloed, but connected to a wide range of subjects in the curriculum; discussing with faculty, joining dedicated labs, and volunteering in research and outreach activities, can integrate climate change in subject matters.

Extracurricular activities beyond the university are crucial to engage and build community. Joining Youth networks focused on climate adaptation, such as YOUNGO and Youth Climate Lab, will connect you to experiences around the world and build a network for adaptation to health consequences of climate warming. Volunteering at local non-governmental organizations to help build community. For example Second Harvest, which is Canada’s largest food rescue charity. Second Harvest offers volunteering opportunities where you can advocate for the reduction of food waste, a more sustainable supply chain, and access to nutritious food.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to our supervisor, Dr. Idil Boran, for her continued guidance and contributions on this project. We would also like to extend our special thanks to the members of the Synergies of Planetary Health Research Initiative and Lab for their suggestions on an earlier draft, including Maryam Bagherzadeh and Marlie Whittle.