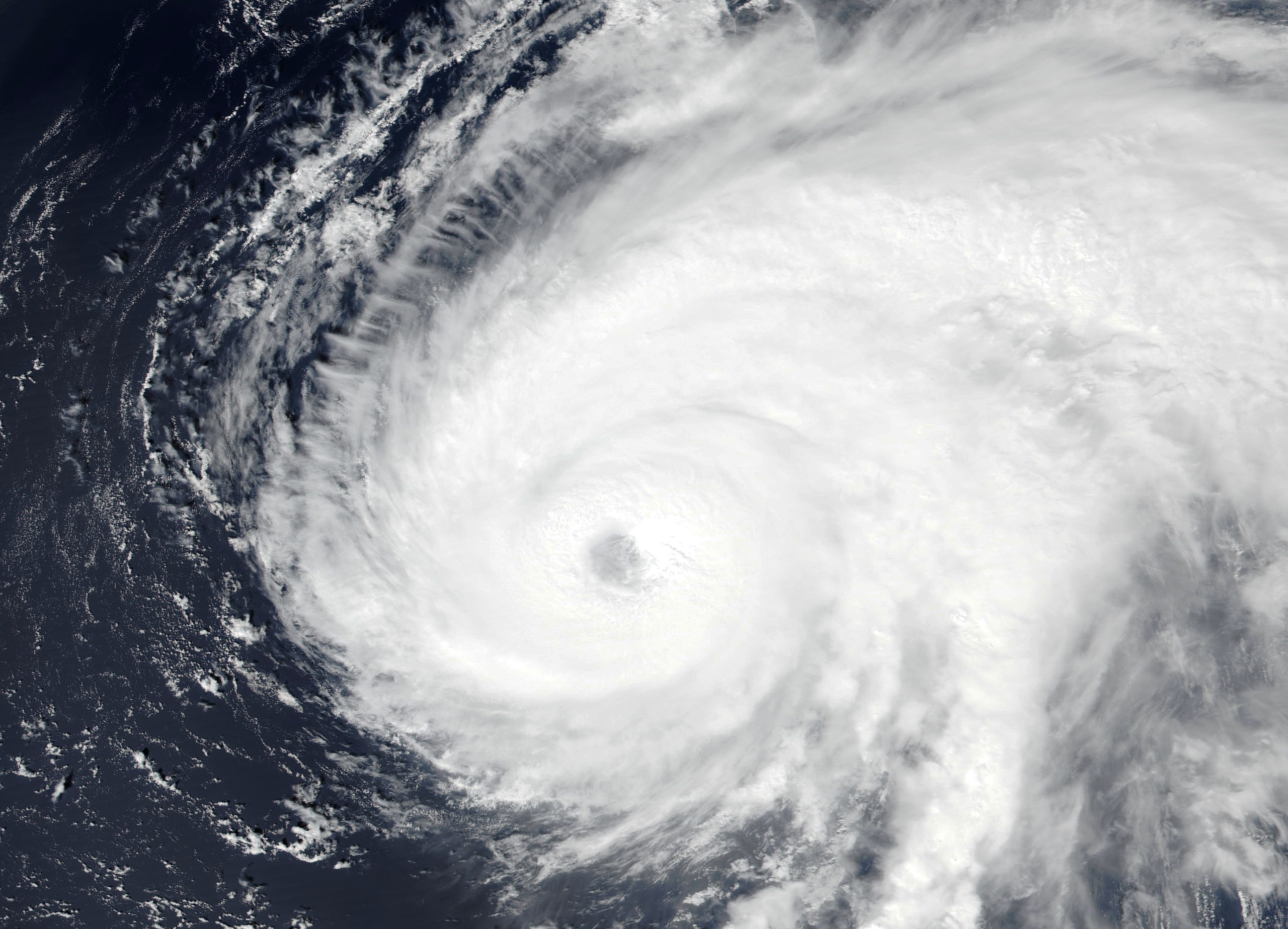

Estimated to have caused over $700,000,000 in damages, Hurricane Fiona was the costliest in Canada’s history. It first made landfall in Nova Scotia on Sept. 23 as a category two hurricane with maximum wind speeds of 165km/h. Canada has dealt with post-tropical storms in the past, however, the intensity Fiona maintained as it wiped through the Atlantic coast is what made it unique.

York Atmospheric Science Club (YASC) president and fourth-year atmospheric science student, Dylan Kikuta, provides insights on hurricane formation. “Typically, hurricanes thrive on warm waters, limited shear (amount of wind speed and direction change with height), and an abundance of atmospheric moisture. […] However, Hurricane Fiona was different because she was injected with an energy boost from another weather system. As she tracked northeast, a weather system swept in from northwest and caught Fiona just as she was beginning to enter cooler waters. This process, called phasing, amplified meteorological processes and enabled her to maintain intensity despite the increasingly hostile environment for hurricanes.”

Fiona was Canada’s second category two hurricane in the last 20 years, the other being Hurricane Juan when it hit Nova Scotia in 2003. As well as leaving up to 500,000 residents without power, the storm is said to have caused significant damage, from flooded homes to claiming two lives. With such devastating results from Hurricane Fiona, questions have risen toward the effects of climate change on the intensity and frequency of weather events like these.

Dr Gary Klaassen, professor at Lassonde School of Engineering at York University, explains that, “Hurricane formation is a complex process involving wind shear and condensational heating. They’ve been forming since historical records were started, so it’s not possible to attribute any particular storm to climate change.

“From data going back to 1975, Holland and Bruyere (“Climate Dynamics 2013”) found no trends in the overall frequency of hurricanes, but they did find a 25 to 30 per cent increase in the number of stronger Cat 4 and 5 storms — later studies have been consistent with that result. So while the overall number of hurricanes per year is not increasing, there is evidence that the number of the strongest hurricanes is increasing under climate change.”

Dr Klaassen has a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in atmospheric physics from the University of Toronto and a B.Sc. in physics from the University of Waterloo. His research involves investigating small-scale flows and their interactions with weather and climate systems, as well as the larger scales associated.

Assistant Professor at the Department of Earth and Space Science and Engineering, Neil Tandon, adds, “Storms with the intensity of Fiona are not unprecedented in Atlantic Canada, and we have not seen evidence that the frequency of hurricanes overall has gone up. There is evidence, however, that when hurricanes do occur, their intensity is getting stronger as temperatures rise. So as temperatures increase, we can expect that a greater proportion of hurricanes and post-tropical cyclones (storms originating from hurricanes) will have the intensity of Fiona.”

While equating climate change as the sole cause of Hurricane Fiona would be a hasty assumption, Professor Tandon does explain that, “As temperatures rise, basic thermodynamic principles dictate that there is an increase in water vapour in the atmosphere. Over most of the globe, this increase in water vapour is resulting in more precipitation and more flooding during extreme storms.”