Founded by a group of medical students and master’s of public health candidates, four individuals at Translations 4 Our Nations (TFON) have led a global initiative in translating COVID-19 resources into more than 40 Indigenous languages from over 30 countries. The initiative partnered with Indigenous communities during the pandemic to facilitate the accessibility of health information, and eventually, launch a free website.

Reviewed by Harvard doctors, Harvard medical students, and Indigenous youth leaders from the UN Global Indigenous Youth Caucus, the material that the initiative has translated aims to provide the Indigenous community with important information about health safety and COVID-19 in their native languages. It is entirely community- and Indigenous-led.

Victor Anthony Lopez-Carmen, founder and second-year medical student at Harvard Medical School, says: “I founded this initiative because I saw how my own Indigenous communities struggled with lack of COVID-19 information that was in their language or culturally relevant to their contexts.”

During the early stages of the pandemic, the United Nations’ Department of Economics and Social Affairs reported a complete lack of “relevant information about infectious diseases and preventive measures” in Indigenous languages internationally.

Even one case in an Indigenous community is concerning because “these communities are among the most vulnerable to COVID-19 due to distances, access to necessary resources, and underlying health conditions.”

Co-founder Sukhmeet Singh Sachal, a second-year medical student at the University of British Columbia, echoes Lopez-Carmen’s sentiments in noticing the disparity between COVID-19 information and its accessibility. “People were being left behind due to language barriers. So bringing these two things together, Translations 4 Our Nations was born,” Sachal says.

Both Lopez-Carmen and Sachal have a master’s degree in public health from Western Sydney University and Western University, respectively.

For co-founders Thilaxcy Yohathasan and Sterling Stutz, both York alumnae and master’s of public health in Indigenous health candidates at the University of Toronto, this initiative resonated with them personally, as they are both settlers on Indigenous lands.

“Many Indigenous scholars have written about the possibility for COVID-19 to exacerbate existing health disparities. This project is international in scope and allows myself, as a student living and working in Toronto, to connect with and build relationships with Indigenous peoples around the globe,” Stutz says.

Founder Victor A. Lopez-Carmen (bottom left) and Co-founders Sukhmeet Singh Sachal (top left), Thilaxcy Yohathasan (top right), and Sterling Stutz (bottom right). (Courtesy of Sukhmeet Singh Sachal, Instagram)

In April, Dr. Theresa Tam, Canada’s chief public health officer, stated that outbreaks in high-risk areas susceptible to rapid spread are of high concern. Even one case in an Indigenous community is alarming because “these communities are among the most vulnerable to COVID-19 due to distances, access to necessary resources, and underlying health conditions,” Tam said in a press conference.

The Federal Minister of Indigenous Services Marc Miller echoed Tam’s concerns in a separate press conference, stating that Indigenous communities could be more greatly affected by an outbreak due to various systemic inequities.

Evidently, accessibility to this type of health information, including education, has been an ongoing problem for Indigenous people. Rachelle Naomi Beswick, treasurer and acting co-president for Aboriginal Students’ Association at York, states: “We speak over 70 different languages from coast to coast, many of our communities are only accessible by plane and the majority overall are remote which makes access to technology and connecting to resources a huge challenge.”

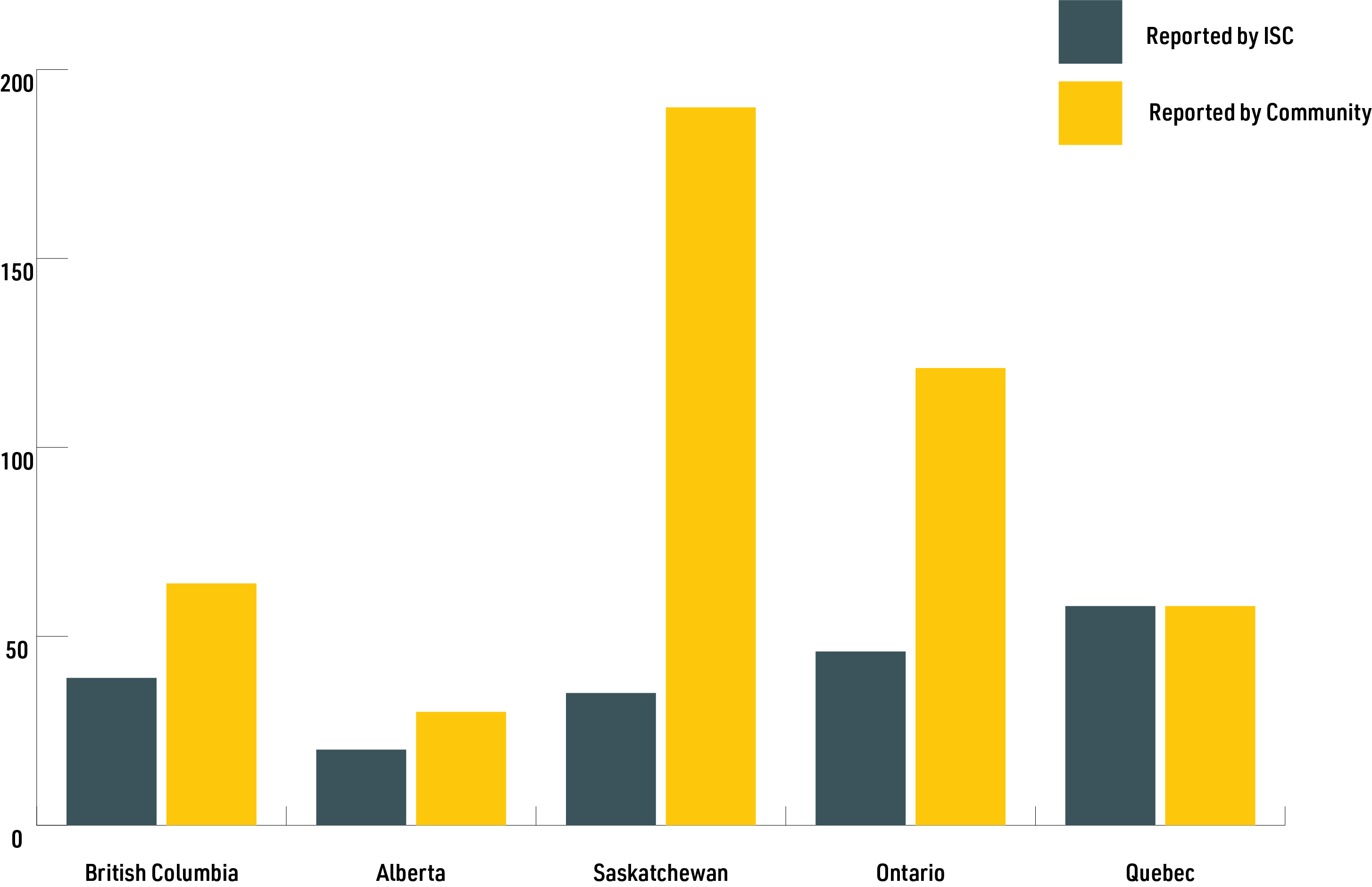

A comparison of COVID-19 cases in mid May reported by Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) versus the Indigenous communities. Yellowhead Institute notes that “this analysis does not include regions with insufficient data to compare. ISC is only providing updates for First Nations on-reserve in five provinces.” (Courtesy of Yellowhead Institute)

Yohathasan believes it necessary to act as a supporter for her fellow Indigenous communities. “Growing up, it was difficult to bring documents that were not in basic English from school to my parents who did not understand much written English. The gap of translated COVID-19 documents is something that needs to be addressed quickly, to mitigate further negative health outcomes for communities that are unable to understand English.”

Since April, TFON has gathered a team of over 120 Indigenous translators from over 30 countries to help make necessary and important information accessible during the pandemic. According to Yohathasan, this is the most diverse group of Indigenous translators ever to unite.

The initiative has provided the following four documents — all translated but also available in English and Spanish — outlining important COVID-19 related information: Emergency Signs (pertaining to symptoms); Information for Indigenous Children; General Information for Indigenous Elders; and Traveling to Cities and Populated Areas. A new document titled “Pandemic and Nutrition” is currently in the works to be translated next.

The languages used for translation range from Greenlandic, Hawaiin, Yaqui, and Swahili to Isixhosa, Maya K’iche’, Tok Pisin, and Zambian sign language, to name a few.

“It is our right to know the complete information and safety measures on COVID-19 in our Indigenous language. When we know safety measures in our own language, we can protect ourselves and effectively teach community members too. Therefore, the information is important for us,” said Kirat Kulung translators Kalpana Kulung and Jok Raj Kulung.

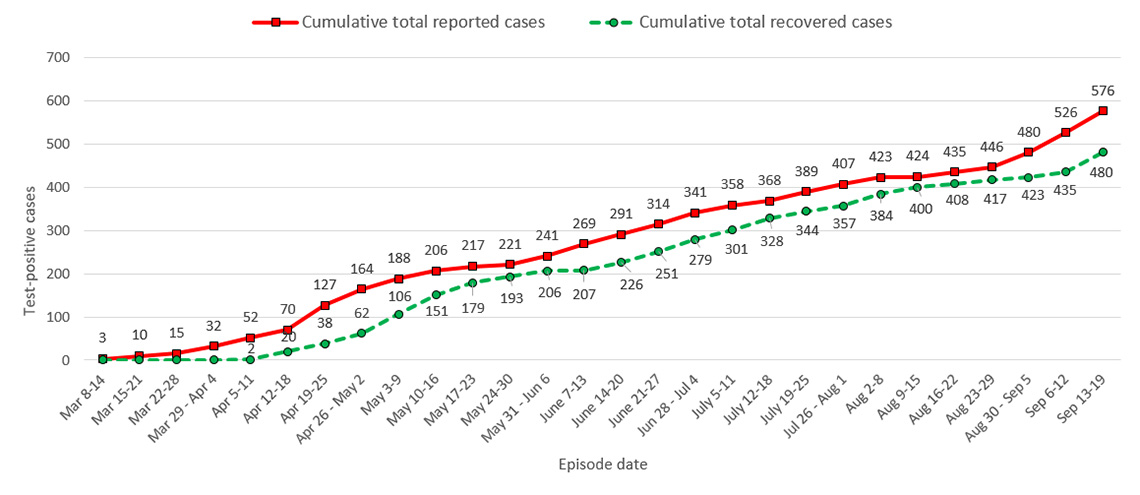

Canada’s cumulative total number of reported and recovered COVID-19 cases in Indigenous communities by case status and date. (Courtesy of Government of Canada)

TFON both originated their resources and had it reviewed by medical professionals. However, not all of the information has been verified for accuracy in translation by medical professionals who speak those languages, and TFON encourages those who find inaccuracies to notify them immediately.

Considering the amount of misinformation about COVID-19 making its way online and circulating amongst social discourse, both accurate and accessible information about the virus and its remedies may be the difference in saving a life.

Endorois translator Carson Kiburo echoes these sentiments when he stated that COVID-19 information can help “save a lot of vulnerable communities from the spread of the pandemic.”

Beswick believes this initiative is important, and deems it exciting. “It would be great to be this expanded to Indigenous languages here on Turtle Island as well, especially as our communities are at a disadvantage with technology, connectivity and overall access.”

According to Beswick, students at York have expressed “mounting responsibilities and tensions in their homes and communities as a result of the pandemic,” citing stressful distractions and various priorities to juggle.

Our languages are our root. Our communities are already very marginalized, if we don’t try to save our languages they will go extinct very soon.

“Returning home can often reunite students with a variety of triggers and demands. Mental health continues to be at the forefront for many Indigenous students who are often caregivers for parents, their own children, and other community members as well,” Beswick continues.

Translators at TFON share similar angst brought on by the pandemic. Bemba translator Julius Riley said: “Information is the most important element in fighting COVID-19 and more importantly, adhering to guidelines in order to make the world a better place!”

These guidelines, of course, must be attainable and understood first — the very gap TFON aims to bridge.

For the elder Indigenous translators, along with the aforementioned health-safety priorities, an additional goal is to preserve the sanctity of their dialect.

“Our languages are our root,” stated Aungkyajai Marma, Marma translator. “Our communities are already very marginalized, if we don’t try to save our languages they will go extinct very soon. We, elders, need to work hand in hand with youths to save it and need to find ways to revitalize them for the future generation.”

However, the creation of this initiative didn’t come without its difficulties — one of them being outreach. Although mediums were available for translators to speak with TFON, time zones proved to be a challenge along with “infrequent communication for translators who reside in spaces without constant internet connection or are only able to access a computer once a week or more.”

What is important to note about community work is that the community knows what works best for them.

Considering the global scale the initiative took on, another difficulty outlined by the TFON founding team was how the pandemic itself impeded on building stronger relationships with the translators. Communication, as with most activities nowadays, was conducted remotely and/or online. “However, some of the translators have been in touch with us after submitting translations and have updated us on the status of their community and how the translations are being used. These updates are posted on our social media and the website.”

For Sachal, this collaboration and its outcome was both inspiring and unique, with the goal in mind to help improve health literacy in communities globally. “You could tell how passionate the translators were about improving the health of their communities. I feel blessed that we were in a position to act as a medium and create this database for communities, free of cost.”

“The idea was to work directly with Indigenous community members in the spirit of partnership, and make sure the benefits went back to them and their communities,” says Lopez-Carmen, echoing Sachal’s sentiments.

Working collectively has evidently proven to be effective, especially when including Indigenous members in the early stages of the initiative’s establishment and planning. “What is important to note about community work is that the community knows what works best for them. The role of someone that is not a member of the community is to support in any way that the community sees fit,” says Yohathasan.

Beswick says it best when she reminds us that we are all stronger as a unit. “While this year has been challenging, the solidarity shown has been impactful and I hope we will continue to build momentum and break ground.”

With files from Thilaxcy Yohathasan