Many of us either grew up with Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook and other social media platforms, or we were introduced to it as teenagers. Regardless of the age, as of January 2020, reports show that more than half of the world are social media users.

I was able to get in touch with an expert in the social media field: Digital and Social Media Strategist Martin Waxman — also a LinkedIn Learning instructor and digital marketing adjunct professor at the Schulich School of Business and McMaster University.

Waxman considers himself a “social media idealist” in the sense that he believes the platform has given individuals a voice while also democratizing media and communications.

“One of the greatest things about it is you can share your thoughts, ideas, photos or videos, and be seen and heard, the social part of it,” Waxman says. “Of course, you can’t ignore the darker side of social media, which includes fake news and disinformation, often spread by both people and bots, harassment, algorithmic manipulation that tries to get us to stay connected, bias, and data privacy.”

Instagram is an especially visual medium for sharing photos and ideas — I refer to it as a “digital storefront to life.” Considering that, and with over 1 billion users as of 2020, it’s no wonder that 70 per cent of people search brands on it while 60 per cent inquire about new products.

Consequently, many companies and brands are now utilizing influencers more than ever to promote their products and services. Many big-name influencers have followings that range from 10 to 20 million.

(Courtesy of Sprout Social)

However, you don’t need a following the size of a small country to do some of the work that these bigger name personalities do, and as a result, have an impact.

There’s a subculture of influencers that not many people are aware of, who also put in a lot of work behind the scenes to their influence. Through content creating, editing, and interacting with their audience, micro-influencers oversee a variety of pros and cons involved with their livelihood.

Waxman defined a micro-influencer as “a person — sometimes a professional and sometimes a hobbyist — who has built up an active or engaged following on social or digital media of between 10,000 to 100,000 people, and who regularly creates content that engages, entertains, or informs their audience.”

Being an influencer bears a stark contrast to jobs like teaching, accounting, and human resources. Over time, more and more negative connotations are being attached to the job.

During the summer I came across a Cosmopolitan article titled “Being a Micro-influencer Means 50,000 Strangers Know What I Ate for Breakfast” by Sam Feher. That is when I realized that many people aren’t aware that not all micro-influencers operate by the same functionalities.

I wanted to open a conversation about the subculture of micro-influencers that are making an impact through niche-based audiences instead of a generic, aesthetic appeal. And even then, the job isn’t always fun and games.

After reading Feher’s article my biggest question was. “When did these micro-influencers come into prominence?”

Naturally, Waxman had an answer for me: “Traditional media has been hit hard by financial challenges and issues, newsroom layoffs, and diminished reach, in part because of social media. Organizations still want to find ways to reach their audience, and influencers have picked up some of the slack because they have an audience that might be interested in a brand’s products, for example.”

After falling down a rabbit hole, I sought local micro-influencers at York to share their first-hand insights into this world and their potential impact.

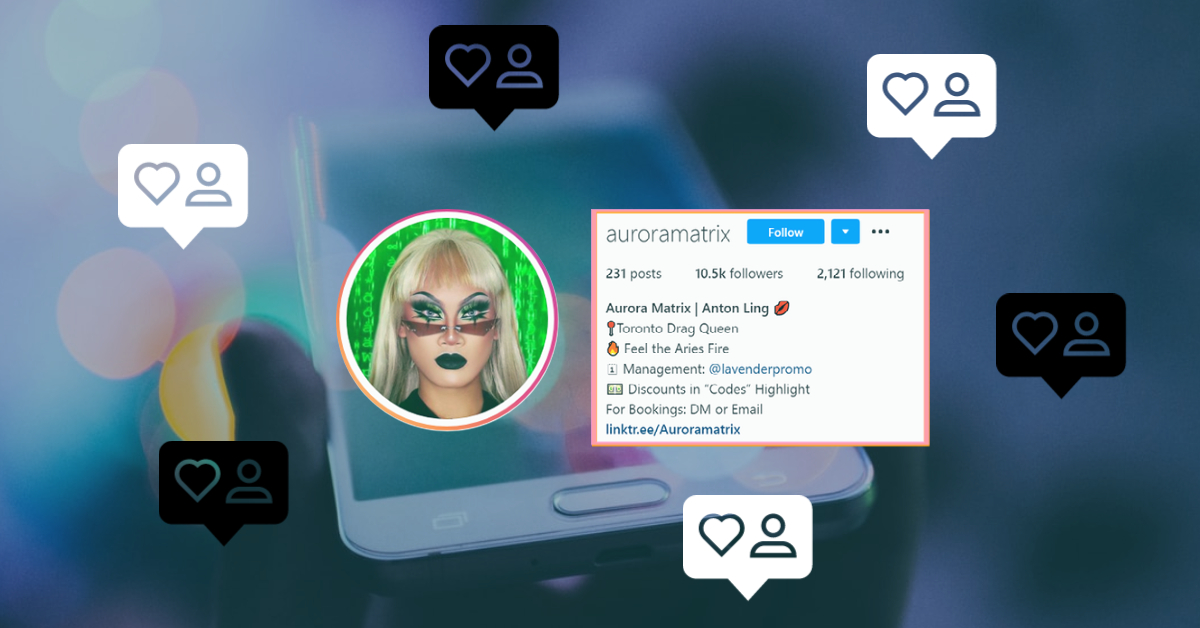

(Courtesy of Anton Ling Instagram / Edited by Victoria Silman)

Anton Ling is a Toronto-based drag queen and a third-year acting conservatory student with over 10,500 followers on Instagram. He recently partnered with major brands like Urban Decay cosmetics and Lush on his Instagram platform.

Ling’s content is mainly directed to fans of the drag community. The majority of his posts centre around drag queens, and looks that he has created or that he experiments with. “My content also revolves around the expression of gender, female impersonation, and performance.”

This focused content is actually what gives micro-influencers a cost-saving appeal to brands — as well as their smaller, but often more engaged audiences. “As a result, it doesn’t cost as much for an organization to work with them and the engagement results might be higher because they’re more closely connected with their audience,” Waxman explains.

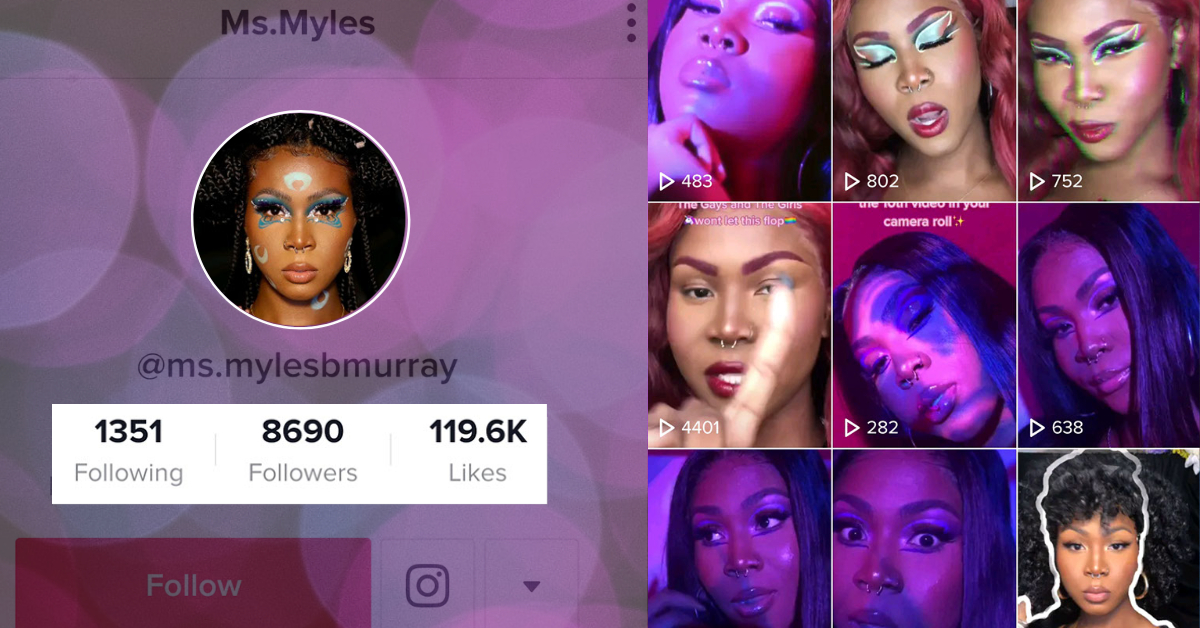

(Courtesy of Myles Bryan-Murray TikTok / Edited by Victoria Silman)

Myles Bryan-Murray, a Toronto-based and self-taught makeup artist, is a former second-year theatre production student with over 8,000 followers on TikTok. She states: “You’ll get companies from all around the world reaching out to you. But I’ve made the decision to hone in on Canadian companies. I keep my market a little niche. As I grow, I have the ability to talk to Toronto.”

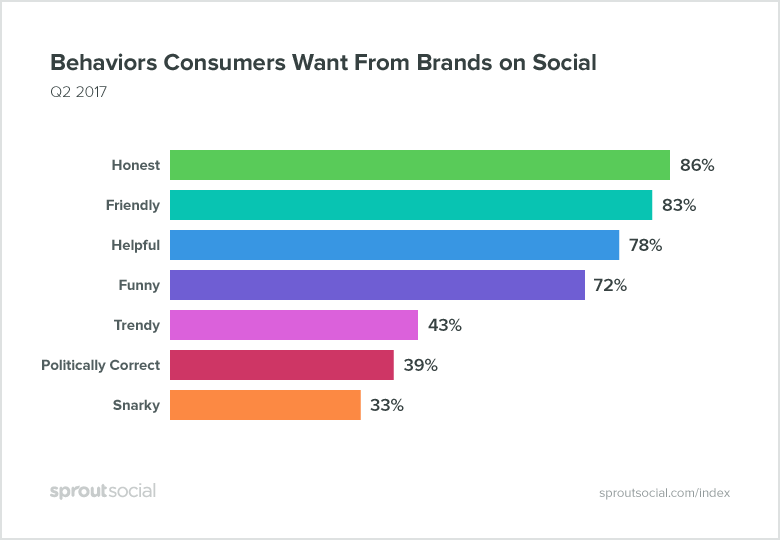

A wide range in influence, of course, comes with its wide range in responsibilities. One of the most important facets being authenticity and trust, considering 86 per cent of people want brands to be honest on social media.

(Courtesy of Sprout Social)

“Authenticity can become a challenge when an influencer is working with a brand and is expected to do certain things that may not seem like it’s part of their personality,” explains Waxman. “Influencers can’t be too commercial or they might lose their audience. They don’t want followers to think they’re just selling products.”

Part of remaining authentic for both Bryan-Murray and Ling is making the time to interact with their followers, likes, comments, and messages. According to Ling, being approachable is a key element to engagement. “If you’re actively reaching out to people and having conversations with them, they’ll be more open to interacting with you.”

Bryan-Murray says her authenticity takes into consideration her local community: “Almost all the companies I’m working with at the moment are currently Toronto-based cosmetic companies, Black-owned, and Canadian-based businesses.”

Bryan-Murray also emphasizes her goals to not follow trends, but rather create her own niche-based trends. “I put my content, voice, and perspective first. I’m very particular about inspiration versus replicating certain makeup looks or certain content from other people.”

Ling, on the other hand, directs his content to incorporating his own culture into his drag, advocating for Queer Asian youths in the hopes to be a role model for younger generations. Part of the role model duty for Ling also involves educating his audience so that they understand what’s going on in the world.

(Courtesy of Anton Ling Instagram / Edited by Victoria Silman)

“During the Black Lives Matter movement and COVID-19, I was constantly posting on my stories and trying to make sure that people are following the rules, and that they know about what is going on in the world. When Pride came around, it was so important that we understood that Pride happened because of a transgender Black woman,” adds Ling.

Similar to how not all negative connotations are true for micro-influencers, the job of one isn’t always 100 per cent glamorous either.

Despite their methods for authenticity, being approachable has its downsides as well. There have been times where Bryan-Murray had to manage followers with “an unhealthy attachment to me” or “that have been very invasive at times.”

There have been times where Bryan-Murray had to manage followers with “an unhealthy attachment to me” or “that have been very invasive at times.”

The job also shifts minute-by-minute based on what’s happening in our digital spheres and what followers want, so this takes its own toll.

“There’s a lot of work and sacrificing that goes into it. It’s hard to balance your real life with social media because you have your obligations,” Bryan-Murray explains. “People should be careful with wanting to be an influencer and how misinformed they might be about the job. It looks glamorous on the outside, but it is hard work on the other side of the screen.”

Waxman drives Bryan-Murray’s point home when he says: “The reality is, in order to do well, you need to put in a lot of hours and continually come up with content. They could feel pressure knowing they constantly have to create and share fresh content.”

The difference between micro-influencers and bigger-named influencers, like Kylie Jenner, is brand attainment methods. Feher wrote that “brands give Jenner tons of stuff hoping she’ll post a blurry five-second thank-you snap (which, fair, would be seen by millions of eyeballs). I, on the other hand, am out here spending hours negotiating contracts and creating content. Every. Single. Day.”

Another dark aspect to the job is its effects on mental health. Waxman states: “If there’s one constant about social media, it’s that there’s often a new app or platform to try, and it sometimes feels overwhelming. I think it’s important to remember you can’t do everything or be everywhere.”

“Influencers could also be harassed or criticized harshly or attacked by trolls and that could hurt or frighten anyone,” Waxman adds.

“So much drama, so much pettiness, so much nasty behaviour.”

Ling shares that he sometimes find comments that either “hit home or really make you uncomfortable or sad.” His advice on dealing with the mental health element to the job is to set boundaries and give yourself time offline. “It’s already tiring, constantly being on the screen. It’s really important to have those days when no one has to know what I’m doing for today. It’s my personal time.”

However, for others like Feher, “my followers really control the action, so it’s not totally up to me when ‘the shift’ is over.”

Bryan-Murray’s struggle with mental health is a personal one when it comes to social media. When she came out as transgender, she went through what she describes as a “very tumultuous time just trying to figure out what my life means now.”

Considering the priority Bryan-Murray has placed on her mental health is also the reason why she stays away from the industry’s most problematic facet, and arguable its biggest drawback, she says there’s “so much drama, so much pettiness, so much nasty behaviour.”

“A lot of the time amongst the big influencers in their spaces, if someone does something socially inappropriate or nasty, people are very hush-hush — they don’t say anything. But it’s oftentimes the micro-influencers who are saying stuff, holding people accountable, and holding each other accountable,” Bryan-Murray claims.

In terms of the industry’s future, Bryan-Murray says that she envisions influencers doing mainstream work such as print or television. She also imagines influencers being partially responsible for how the world changes in regards to social issues and other activist platforms.

“You can have as many numbers as you like, but if you’re not doing something important that’s changing the world around you, what necessarily are you doing with your social media platform?”