Last year, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared York’s Global Strategy Lab (GSL) as the WHO Collaborating Centre on Global Governance of Antimicrobial Resistance (WHOCC).

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research provides the GSL’s funding for research in three areas: antimicrobial resistance, global legal epidemiology, and public health institutions. York provides the lab research space in the Victor Phillip Dahdaleh Building.

According to York’s Advisor & Deputy Spokesperson Janice Walls, the lab has also raised “over $1 million per year in external research funding, making it one of the largest research groups on campus.”

This year, the anniversary of the GSL’s recognition by WHO fell on World Antimicrobial Awareness Week, and on November 18, York hosted a virtual panel. The panelists discussed what WHO has deemed as one of the top 10 global threats to public health: antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

AMR occurs when microbes such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites evolve to the point where they can resist antimicrobial medications. This renders infections, including deadly illnesses, difficult to treat and increases the risk of spreading disease.

Antimicrobial drugs include the following treatments for microbes: antibiotics for bacterial infections, antivirals for illnesses caused by viruses, antifungals for treating infections caused by fungi, and antiparasitics are used against parasites.

However, “microbes, like humans, adapt. Left unchecked we will continue to see a dramatic rise in AMR infections,” stated Paul McDonald, York’s dean for the Faculty of Health, during the panel.

According to a 2016 review on AMR, attested by the WHO in 2019, at least 700,000 deaths occur per year worldwide due to AMR, of which 14,000 are in Canada. However, by 2050, that figure will increase to 10 million people worldwide per year. According to the Canadian Government, that’s more than the current annual mortality rate worldwide for cancer.

In Canada, it’s estimated that the AMR-related death rate by 2050 could be anywhere between 256,000 and 396,000 costing the healthcare system $120 billion.

As such, the WHOCC aims to “bring more attention to the issue of antimicrobial resistance and formulate ways to assess and address it” as well as “focus on the global governance of antimicrobial resistance.”

“Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, York researchers, including those from the Global Strategy Lab, are providing analysis and advice that will help shape government policies and public health practices to protect the health and wellbeing of communities worldwide,” says York President and Vice-Chancellor Rhonda Lenton.

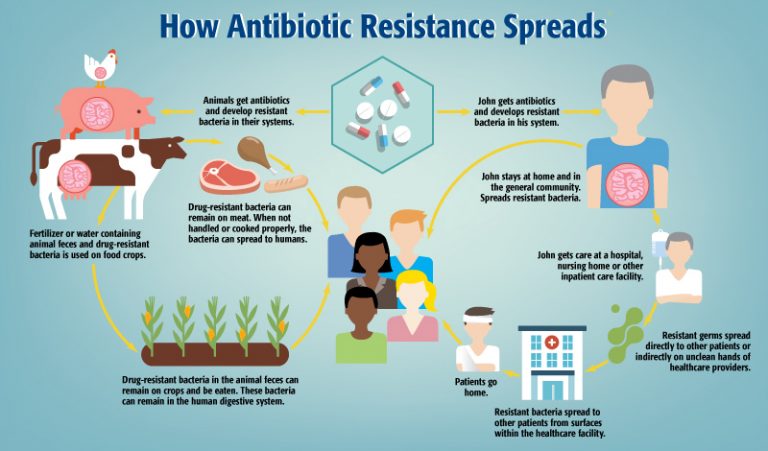

AMR remains a complicated matter since there are many factors that contribute to its occurrence, including “overuse of medicines in humans, livestock, and agriculture, as well as poor access to clean water, sanitation and hygiene,” reads the WHO’s webpage.

According to WHOCC and GSL Director Steven Hoffman, a consequence of modern industrialized farming practices is farmers giving their animals unnecessary antimicrobials as a preemptive measure to the animals getting sick but to also allow proximity between animals. It’s also cheaper than creating “healthy living environments for those animals or having a program where they identify which animals are actually sick.”

“It’s also plants,” adds McDonald. “We use different herbicides, for example, and different organisms attack plants just as they do with people and animals. So then you start to realize that antibiotics are used in food production,” says McDonald.

Evidently, the issue with the spread of AMR is that of a global one — but even if Canada mitigates its national risks, there is nothing stopping microbes from entering the country internationally.

“Just like COVID-19, AMR does not respect borders and has the potential for devastating economic security and sustainable outcomes,” Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer Dr. Theresa Tam stated in the panel. “In taking a One Health approach, Canada is focusing on four key pillars across all sectors: infection prevention control, surveillance, stewardship, and research and innovation.”

Hoffman echoes Dr. Tam’s sentiments, stating that this is an issue “no country can address in its entirety without working with other countries.”

“Microbes don’t carry passports and don’t go through border controls. If other countries don’t simultaneously make those investments then Canada won’t be able to achieve its full benefits.”

“It’s one of those things that equally affect everyone because AMR does not discriminate. Microbes don’t carry passports and don’t go through border controls. If other countries don’t simultaneously make those investments then Canada won’t be able to achieve its full benefits.”

However, not all countries are willing to make those investments. According to Hoffman, we are currently facing a “free rider problem” in the monopoly since antimicrobials is one of the most broken markets. In other words, many countries wait for other countries to invest in medications first from which they will be able to benefit from once it’s on the market.

Hoffman further explains that a country may not want to invest because they perceive that the full benefits of that investment are not directly received for its cost. “It costs essentially nothing to develop a new drug if we all split the cost. But getting that level of global collective action is difficult, although that’s exactly what we do at the lab,” says Hoffman.

“People say, ‘why are we giving money to foreign countries when we have our own challenges?’ While we do have our own challenges, COVID-19 is an example of what happens if you ignore something on a global scale,” says McDonald. “Providing money and foreign aid to build water treatment, improve sustainable farming, build sanitation systems, and improve quality of life and medical care — all things that actually end up helping us as well.”

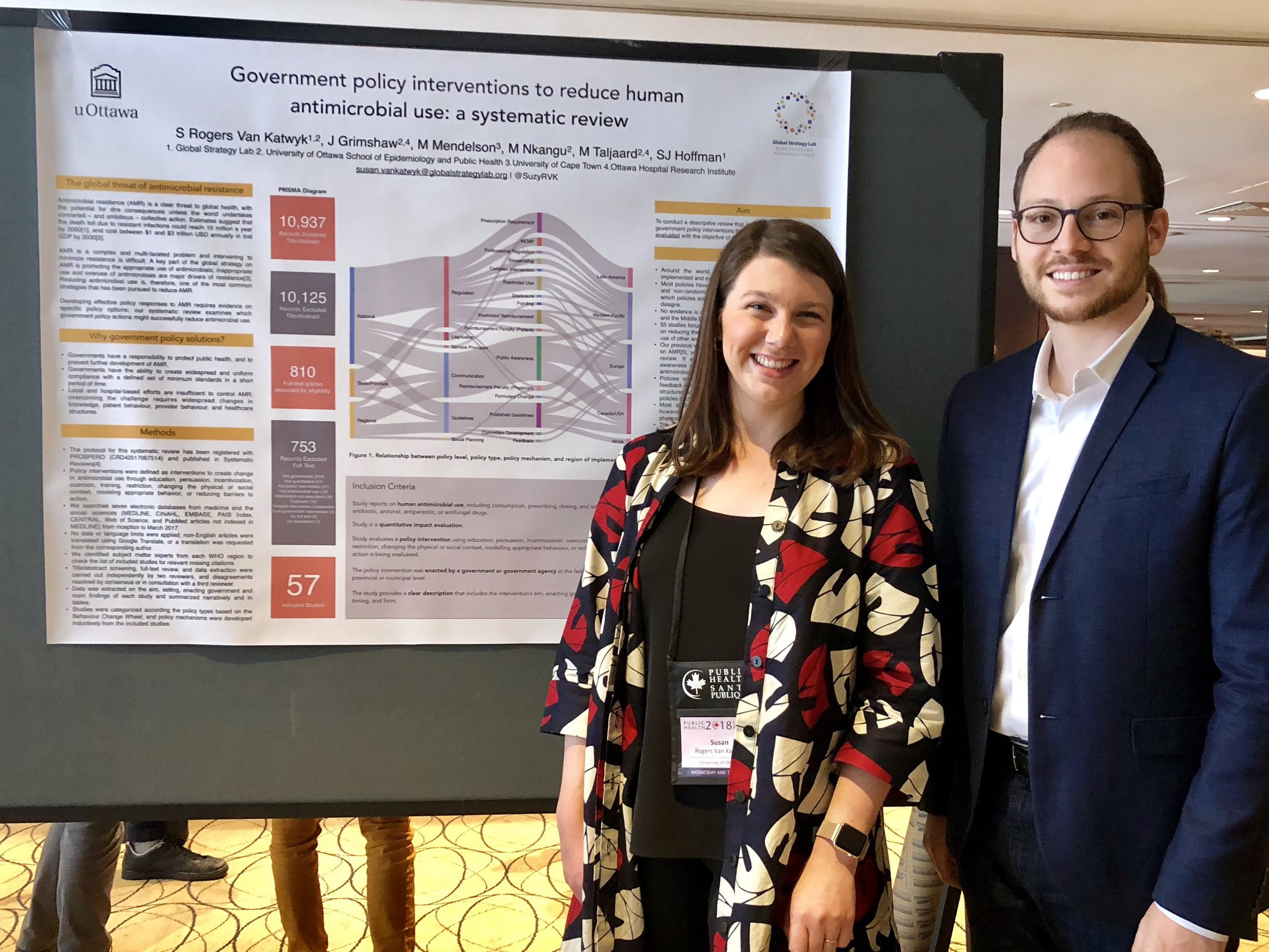

WHOCC Managing Director Susan Rogers Van Katwyk states that progress is slow. “Many countries around the world have developed detailed national action plans, but have been unable to get the funding and government support to put these plans and programs into motion.”

As such, the GSL has identified three challenges when it comes to addressing AMR: lack of access to antimicrobials worldwide, conserving the existing effectiveness of drugs that work, and the innovation of new drugs.

Regarding conservation, international expert Professor Dame Sally Davies stated that it’s crucial we protect what effective medications we’ve got, despite resistance developing regardless.

“We also have to invigorate the pipeline and that’s a big piece of work from research and development, in universities and institutes and start ups, to pull through mechanisms so that big drug companies are incentivized enough to invest in it,” Davies added.

Preksha Rathod, MD Candidate at the Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine (McMaster University), says that antibiotic resistance and resource stewardship are highlighted in their education. “However, I have noticed some differences in what we are taught in lecture versus clinical practices I have observed.”

Rathod states that her curriculum focuses on “only using what you need when you need it.” Microbiology, knowing the bacteria’s spectrum of activity through cultures, “helps decide what antibiotic to use based on what type of bacteria it is and prevents the use of ineffective antibiotics.”

However, one of the common reasons why medications often don’t work is that physicians don’t always get a lab test and treat patients based on common pathogens of that particular illness. “They don’t actually know what that bacteria is that they’re dealing with, so they give medication based on their best guess,” says McDonald.

Rathod attests to this method, contrasting clinical practice’s “knee-jerk approach” to medical school curriculums. “It’s not a perfect practice, but from what I have observed, most physicians try as much as possible to use targeted therapies, but they are limited by the clinical uncertainties and cost effectiveness.”

“We’re very bad at getting doctors to do what they should do and that doesn’t just apply to AMR,” stated Davies. “There’s something about the behavioural sciences education that we haven’t cranked across all of medicine.”

So while researchers and physicians work to battle the risks and increase of AMR worldwide, those who are not a part of the medical community can contribute in their own simple ways as well.

Rogers Van Katwyk and McDonald state that we can begin by asking questions. “The next time you get an antibiotic prescription, ask your doctor whether you really have a bacterial infection and whether antibiotics are the necessary treatment option,” says Rogers Van Katwyk.

The Canadian Government describes unnecessary use of antibiotics as:

- “Taking or being prescribed antibiotics for infections caused by a virus.

- Being prescribed the wrong type, dose or duration of antibiotics.

- Taking antibiotics in ways other than how they were prescribed.

- Taking leftover antibiotics without a prescription or using someone else’s antibiotics.”

Rogers Van Katwyk also advises people to do their part in reducing infection spread in the first place, including washing hands, getting vaccinations, and using a condom. “In Canada, a large proportion of gonorrhea infections are resistant to at least one, if not several, of the available treatments. Protect yourself, wear a condom, and get tested for sexually transmitted infections.”

McDonald advises advocacy and awareness, but beyond that, “we need to be asking where our food comes from and how we can change food supply.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend some simple safety tips to avoid food-related infections and to prevent the spread of resistance.

“But I think the number one thing is people need to demand from their government coherent plans for addressing this challenge,” says Hoffman.

The WHO does not provide funding for the Collaborating Centre and none of the research funding is from companies or entities associated with pharmaceutical companies.